Giant pilomatrixoma in a 12 year-old child

Sahar Vanessa Amiri * and Alessandro Venzo

Department of Burns and Plastic Surgery, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark

*Corresponding author

*Sahar Vanessa Amiri, Department of Burns and Plastic Surgery, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark

Figure 1:Tumour preoperatively.

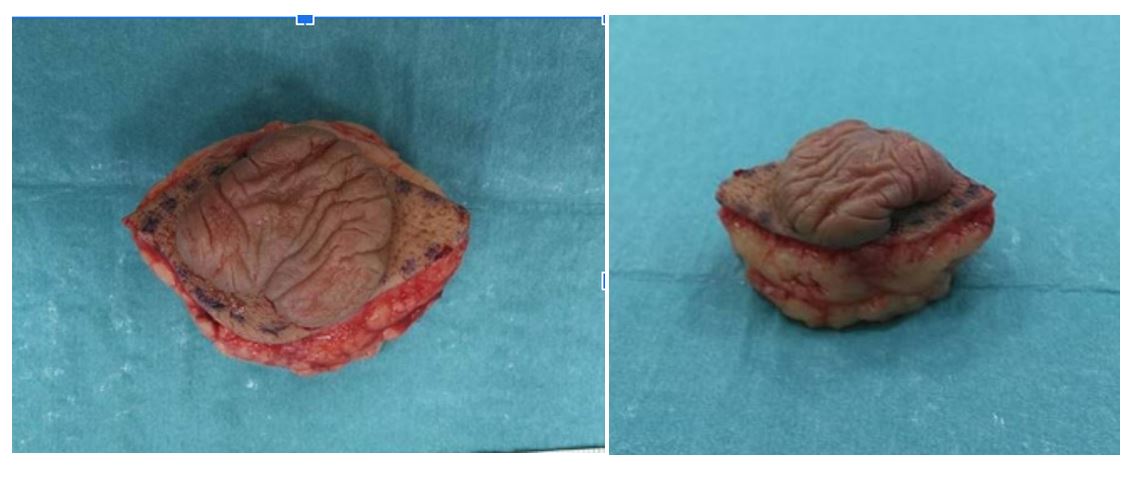

Figure 2: Tumor shrinking after excision.

-

- Jones CD, Ho W, Robertson BF, Gunn E, Morley S (2018) Pilomatrixoma: a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol 40:631–641.

- Zhao A, Kedarisetty S, Arriola AG, Isaacson G (2021) Ear Nose Throat J. 2021:1455613211044778.

- RAAB W (1963) Epithelioma of the sebaceous glands. Archiv fur Klinische und Experimentelle Dermatologie 216: 325-333.

- Laffargue JA, Stefano PC, Vivoda JL, Yarza ML, Bellelli AG, (2019) Pilomatrixomas in children: Report of 149 cases. A retrospective study at two children's hospitals. Arch Argent Pediatr 117(5): 340-343.

- Panda, Sangram K, Sahoo, Pradyumna K, Agarwala, (2023) A systematic review of Pilomatrix carcinoma arising from the previous scar site of Pilomatrixoma. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics 19(5): 1098-1102.

- Pirouzmanesh A, Reinisch JF, Gonzalez-Gomez I, Smith EM, Meara JG (2003) Pilomatrixoma: a review of 346 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 112(7): 1784-1789.

- Sabater-Abad J, Matellanes-Palacios M, Bou-Boluda L, Campos-Dana JJ, Alemany-Monraval P, Millán-Parrilla F (2020) Giant pilomatrixoma: a distinctive clinical variant: a new case and review of the literature. Dermatol Online J 26(8).

- Jones C, Twoon M, Ho W, Portelli M, Robertson BF, (2018) Pilomatrix carcinoma: 12-year experience and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 45(1):33-38.

- Laffargue JA, Stefano PC, Vivoda JL, Yarza ML, Bellelli AG, et al.(2019) Pilomatrixomas in children: Report of 149 cases. A retrospective study at two children's hospitals. Arch Argent Pediatr. 117(5):340-343.

- Levy J, Ilsar M, Deckel Y, Maly A, Anteby I, Pe'er J (2008) Eyelid pilomatrixoma: a description of 16 cases and a review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol 53(5):526-535.