Sarcoidosis Mimicking Metastatic Disease: A Case Report

Zahra Mirfeizi 1,Shadan Tafreshian 2*, Elham Atabati 3 Asal Sadat Azami4 and Shaarbaf Eidgahi 5

1Professor of Rheumatology, Rheumatic Diseases Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2967-2404

2Rheumatology fellowship, Rheumatic Diseases Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

3Associated Professor of Rheumatology, Rheumatic Diseases Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2568-2602

4Assistant Professor of Rheumatology, Rheumatic Diseases Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8745-1271

5PhD of Biostatistics, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2622-3627

*Corresponding author

*Shadan Tafreshian, Rheumatic Diseases Research Center (RDRC), ImamReza Hospital, ImamReza Square, Mashhad; Iran

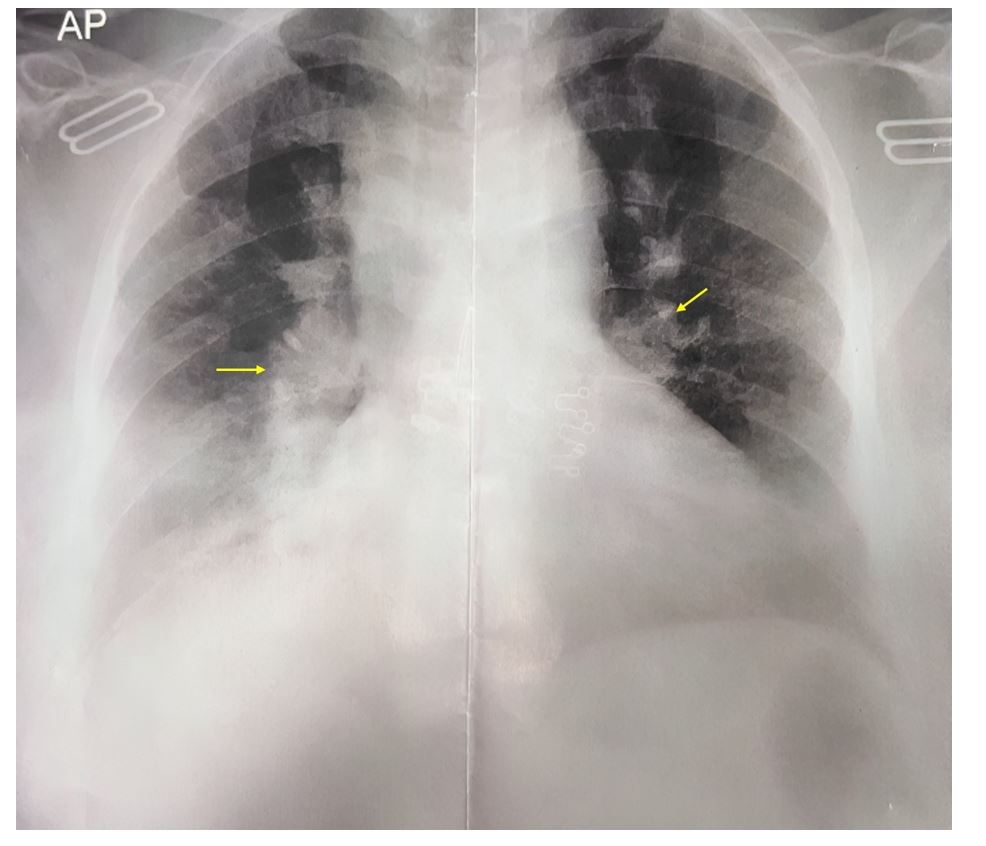

Figure 1:Chest X-ray of a 64-year-old female with a persistent non-productive cough, showing prominent hilar structures (yellow arrows) and hazy opacities in the lower lung zones, suggestive of a granulomatous or infiltrative process.

Figure 2:Sagittal lumbar spine MRI showing degenerative changes, reduced disc height, grade 1 spondylolisthesis at L4–L5 and L5–S1, and sclerotic lesions at L1 (yellow arrow) and posterior superior L5.

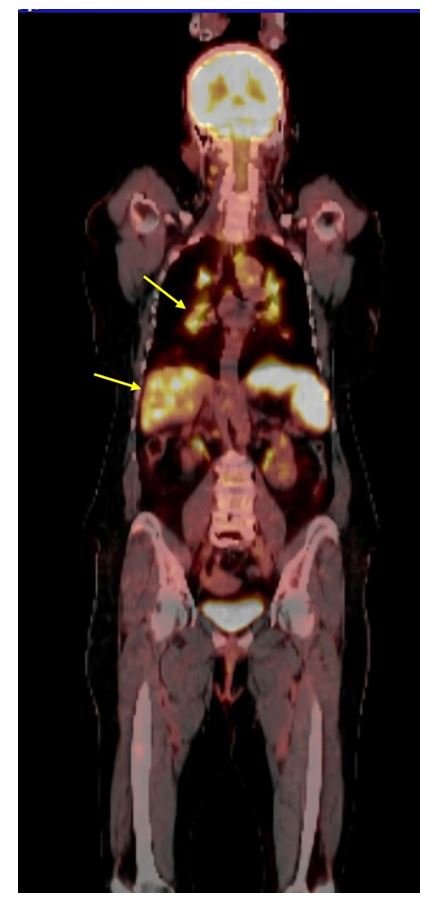

Figure 3:PET scan showing extensive hypermetabolic lesions with hepatic and splenic enhancement (yellow arrows).

- Cohen PR, Kurzrock R (2007) Sarcoidosis and malignancy. Clin Dermatol. 25(3):326-333.

- Iannuzzi Michael C, Rybicki Benjamin A, Teirstein Alvin S Sarcoidosis. New England Journal of Medicine.357(21):2153-2165.

- Valeyre D, Prasse A, Nunes H, Uzunhan Y, Brillet PY, Müller-Quernheim J (2014) Sarcoidosis. Lancet 83(9923):1155-1167.

- Ebrahimzadeh F, Samadi S, Mirfeizi Z, Hashemzadeh K (2024) [A clinical overview of sarcoidosis: Pathogenesis, symptoms, diagnosis and treatment]. J Birjand Univ Med Sci. 2024; 31(1): 1-14. [Persian]

- Ungprasert P, Crowson CS, Matteson EL (2017)Risk of fragility fracture among patients with sarcoidosis: a population-based study 1976-2013. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28(6):1875-1879.

- Baughman RP, Lower EE, du Bois RM (2003) Sarcoidosis. Lancet. 361(9363):1111-1118.

- Brincker H (1986) Sarcoid reactions in malignant tumours. Cancer Treat Rev. 13(3):147-156.

- Ferjani HL, Rahmouni S, Nessib DB, Triki W, Maatallah K, Kaffel D, Hamdi W (2022) Vertebral sarcoidosis: diagnosis to management. Acta Orthop Belg. 2022;88(4):655-660.

- Baughman RP, Janovcik J, Ray M, Sweiss N, Lower EE (2013) Calcium and vitamin D metabolism in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 30(2):113-120.

- Orcel P, Funck-Brentano T (2011) Medical management following an osteoporotic fracture. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 97(8): 860-869.