Case 1

The patient was born at 40 weeks of gestation via a normal spontaneous delivery (weight: 2,763 g at 40 weeks). His family history was unremarkable. No abnormalities were detected in his metabolic screening test at birth. PDA (patent ductus arteriosus) ligation and aortic elevation were performed on the 14th day after birth. Thereafter, the patient was managed under artificial respiration, and a tracheostomy was performed at 4 months of age because of chronic respiratory failure. Tube feeding using elemental diet (Elental®) was also performed because of insufficient feeding. He had ear deformities and specific palm characteristics. He also had low-set ears, micrognathia, left postnasal closure, and micropenis. He had no underlying cardiac abnormalities associated with CHARGE syndrome other than the treated PDA. Quadriplegia was present since the neonatal period. At the age of 1 year, genetic testing identified a CHD7 gene mutation by direct PCR, and he was diagnosed as having CHARGE syndrome. He had no thymic hypoplasia or infections suggesting impaired T-cell function. He had no past history of recurrent OMA or pneumonia.

When the patient was 3-years old, he developed a fever of 39 °C. Respiratory disturbance became prominent, and his nasal discharge was positive for the RSV antigen. On admission, his height was 68 cm (−8.1 SD), weight was 6.6 kg (−4.6 SD), and body temperature was 40.8 °C. His blood pressure was 94/42 mmHg, and respiratory rate was 42/minute. His SpO2 was 88% (O2 per liter). His breath sounds showed inspiratory and expiratory stridor. His heart sounds were intact, and hepatosplenomegaly was not observed. He showed unconsciousness (Japan Coma Scale (JCS) 200), mild hypersensitivity of deep reflexes, and intermittent involuntary movements.

His white blood cell count was 12,200/μL (neutrophils: 88.7%; lymphocytes: 6.9%). Hemogloblin was 8.9 g/dL, and platelet count was 125×103/μL. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and γ-GTP levels were 5,482 IU/L (normal range: 13–30), 978 IU/L (normal range: 0–42), and 118 IU/L (normal range: 13–64), respectively. His creatine kinase (CK) level was high at 372.3 IU/L (normal range: 59–248). Total bilirubin was 0.86 mg/dL (normal range: 0.4–1.5), whereas ALP was 831 U/L. Albumin was 3.9 g/dL. BUN and creatinine were 50.8 mg/dL (normal range: 8–20) and 1.2 mg/dL (normal range: 0.65–1.07), respectively. CRP was high at 5.8 mg/dL (normal range: 0.00–0.14), and IL-6 was 320 pg/mL (normal range: 0.0–6.0). Clotting time was abnormal (PT-INR: 2.27; PTT 36 sec.). D-dimer and FDP (fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products) were within the normal range. Ammonia was normal at 42 μg/dL (normal range: 15–45). Urinalysis showed hematuria and proteinuria with high myoglobin levels (more than 3,000 ng/mL). Furthermore, transient loss of consciousness, hepatic and renal dysfunction, and coagulation abnormalities were observed. The patient was diagnosed as having rhabdomyolysis associated with RSV infection.

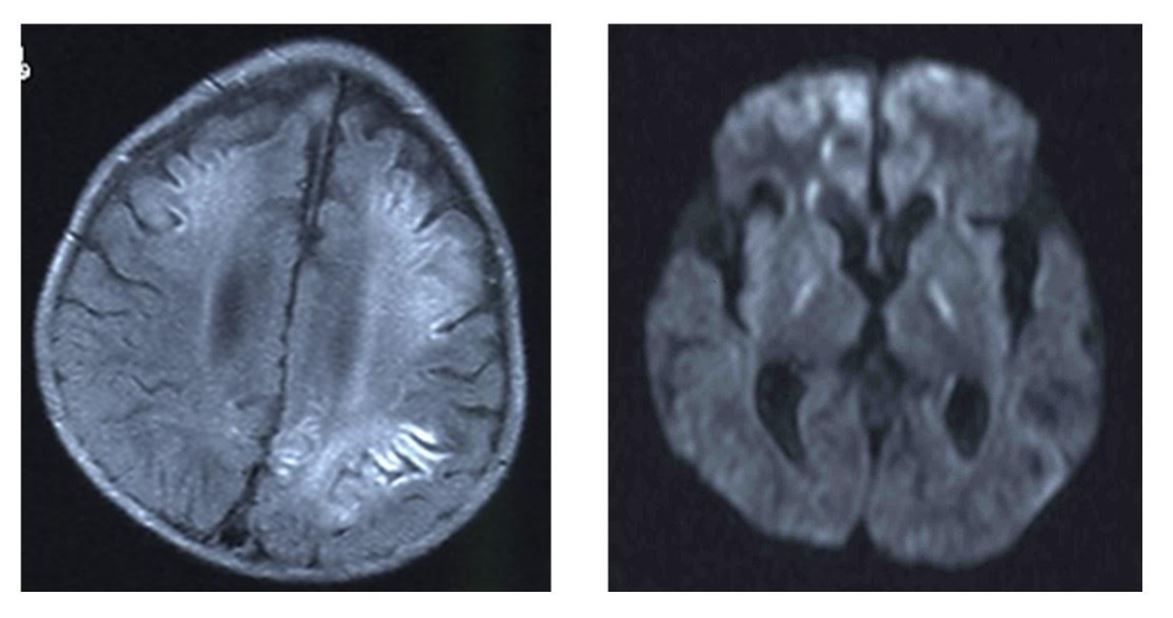

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis yielded normal results, including IL-6 and viral culture. However, LAMP (Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification) for RSV in the CSF was positive for RSV type A. Conventional bacterial culture was negative. Lactic acid and pyruvic acid were normal in the CSF and blood. Analysis of organic acids in the urine showed the increased excretion of adipate, 3-OH-sebacate, and 3-OH-dodecanedioate. He had secondary carnitine deficiency; his free carnitine was 10.92 μM (standard value: 45.6 ± 11.0 μM) and acylcarnitine was 3.93 μM (reference value: 16.2 ± 7.6 μM). Brain MRI displayed a high signal, which was compatible with the encephalopathy observed by diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) (Figure 1).

Apparent high signal images are shown in diffusion-weighted MRI image. (left: FLAIRimage), (right: diffusion-weighted MRI).

Based on his unconsciousness, DWI-MRI findings, and laboratory data, the patient was diagnosed as having metabolic encephalopathy. Intensive treatment with gamma-globulin (2.5 g/kg IV for 1 day), methylprednisolone (1 mg/kg 3 times/day IV for 6 days and tapering for 5 days), and L-carnitine (50 mg/kg IV for 14 days) was performed, and his symptoms gradually improved. Transaminase and CK levels were normalized within 5 days. He showed spastic paralysis and displayed hypoperfusion of the brain on single-photon emission computed tomography. His spastic paralysis has remained unchanged for 5 years.

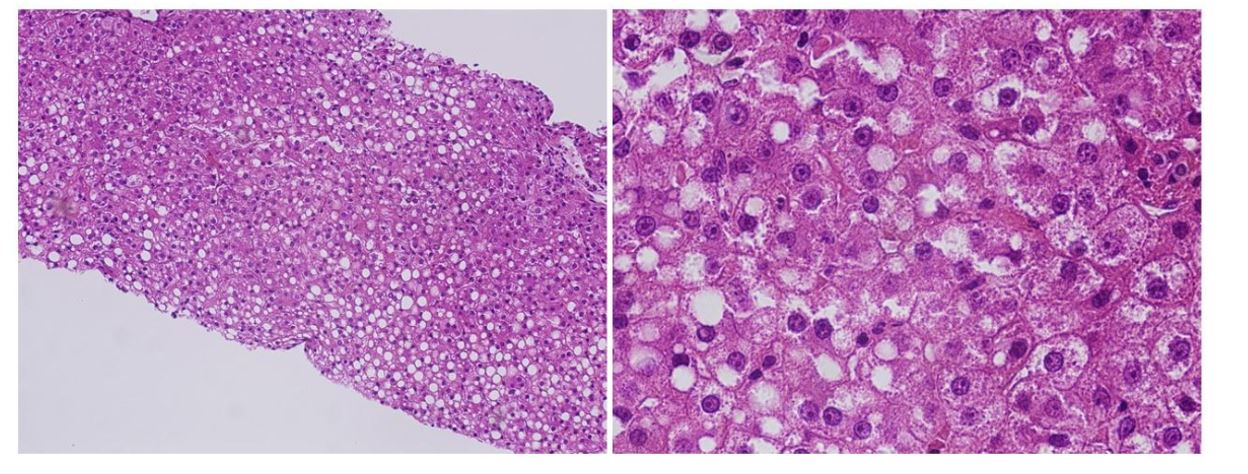

Liver analysis was performed 8 days after admission. Liver pathology revealed mild infiltration of inflammatory cells. There was neither fibrosis nor cholestasis. Prominent accumulation of lipid droplets of various sizes was observed (Figure 2).

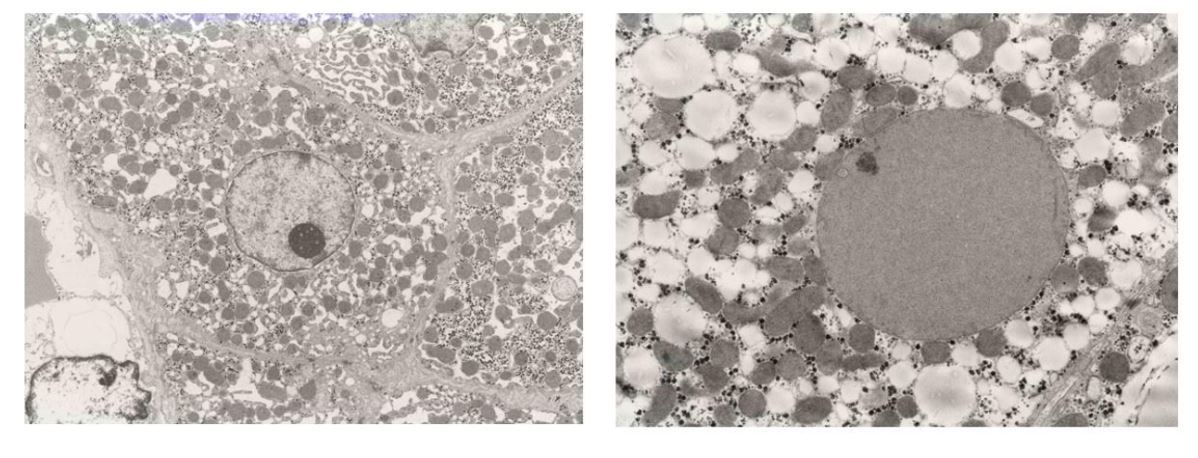

Prominent accumulation of lipid droplets of varying sizes were observed. In the 2,500 X electron microscopy images of the liver, lipid droplets of various sizes were distributed almost uniformly within the cytoplasm of liver cells, together with the almost complete disappearance of intracellular structures (Figure 3).

Intracellular structures (cristae) of the mitochondria were almost completely absent.

Case 2

A 5-year-old girl with CHARGE syndrome, characterized by PDA, right-sided aortic arch with aberrant origin of the left subclavian artery, mitral valve regurgitation, bicuspid aortic valve, left peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis, patent foramen ovale, right thumb polydactyly, bilateral microtia, left low-set auricle, bilateral profound hearing loss, and type 1 laryngomalacia, experienced recurrent severe hypoglycemia triggered by infections and surgical stress. At 2-years old, she developed bronchial asthma exacerbation and hypoglycemia (23 mg/dL), and at 3-years old with COVID-19 infection and hypoglycemia (27 mg/dL), and later that year she developed acute encephalopathy and right hemiparesis owing to profound postoperative hypoglycemia (< 20 mg/dL) following laparoscopic fundoplication. The patient’s new K-type developmental quotient (DQ) was 27 (motor: 28; cognitive: 29; language: 19). Secondary carnitine deficiency was identified and treated with L-carnitine supplementation, after which at 4-years old she experienced seizures with hypoglycemia (33 mg/dL) during acute gastroenteritis, which prompted the initiation of cornstarch therapy.

At 5-years old, she was admitted with a fever and respiratory distress owing to RSV infection (confirmed by antigen testing), requiring CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure ) support. During this time, hypoglycemia did not recur, presumably owing to the continuous L-carnitine and cornstarch therapy, although liver dysfunction (increased AST, ALT, and γ-GTP levels) was observed. She subsequently recovered without any complications.