Louis-Bar syndrome is a primary immunodeficiency (PID) caused by a mutation in the ATM gene (Ataxia Telangiectasia Mutated), which is involved in many critically important cellular processes [1]. Around a damaged area of DNA, the MRN complex (Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1) forms and activates the ATM kinase. In turn, activated ATM kinase participates in cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and DNA repair mechanisms [2].

An important marker of Louis-Bar syndrome is alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), which is produced by the fetal liver and normally ceases after birth [3]. The synthesis of AFP is suppressed by P53, and the activation of P53 is significantly dependent on ATM [4,5]. Another hallmark of the syndrome is a reduced number of T and B cells. This is due to the physiological DNA breaks that occur during T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement in T cells and class-switch recombination in B cells-processes in which ATM plays a crucial role in repairing the breaks [6].

The prevalence of Louis-Bar syndrome varies significantly by country, ranging from 1 in 40,000 to 1 in 300,000 individuals [7]. It is worth noting that among the patients we studied with suspected PID, pathogenic mutations were identified in 12 individuals-among them, 2 had homozygous and 2 had heterozygous mutations in the ATM gene. The most common clinical manifestations include progressive cerebellar ataxia, dysarthria, characteristic facial features, telangiectasia, and frequent infections [8]. Since ATM plays a crucial role in DNA repair, its deficiency is associated with an increased risk-up to 25%-of developing cancer [9]. Despite being inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, even heterozygous ATM mutation carriers have a higher risk of developing cancer and cardiovascular diseases, leading to a reduced life expectancy [10]. Patients with Louis-Bar syndrome require regular immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

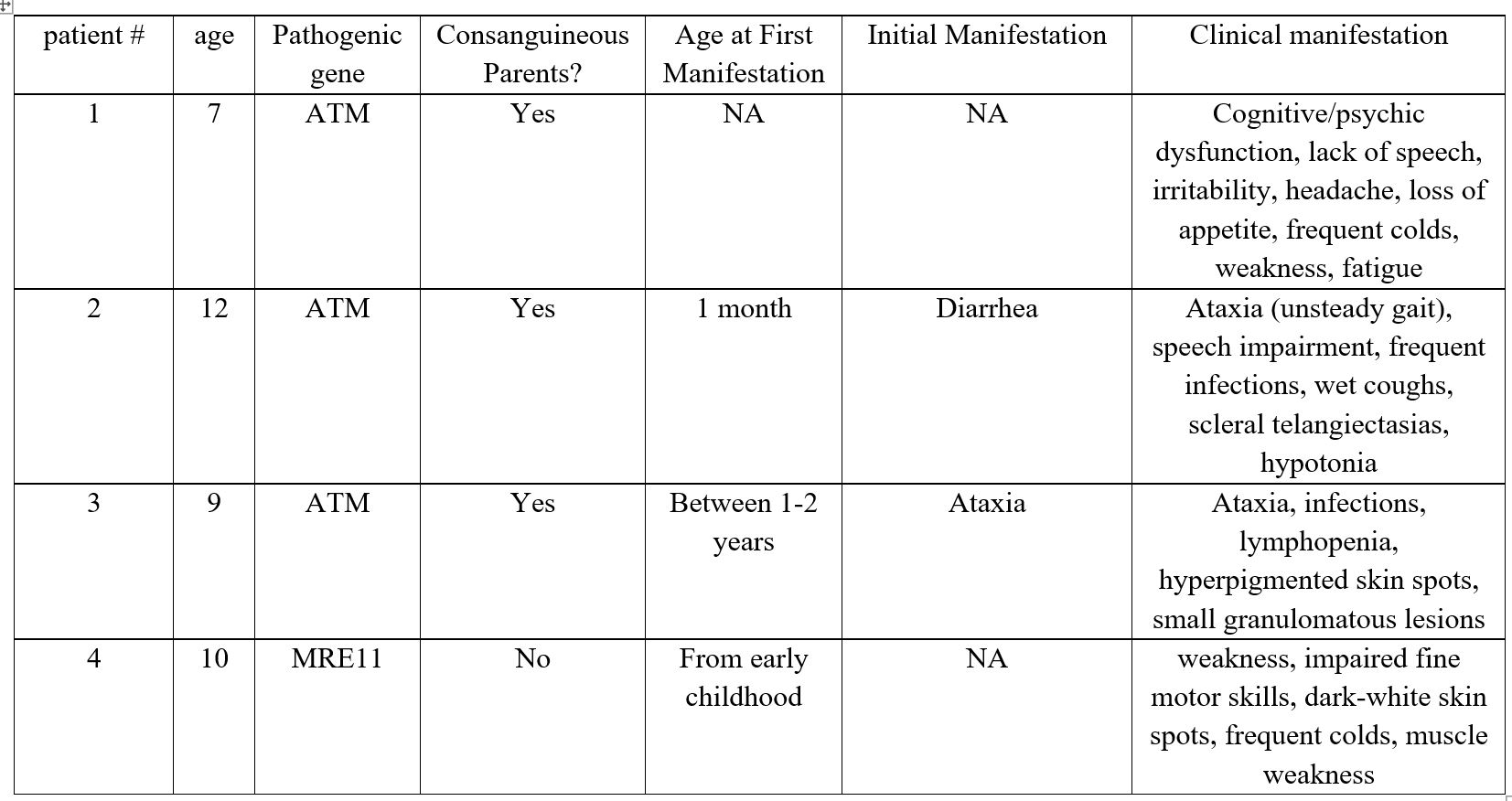

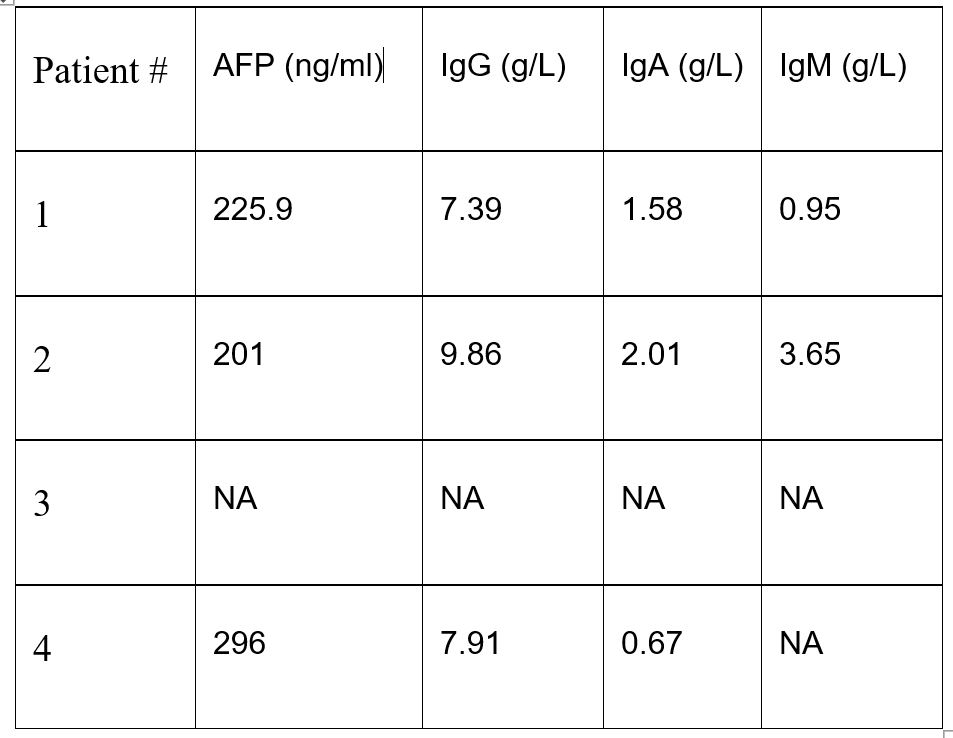

Here we present two cases related to Louis-Bar syndrome, one carrier and one patient with ATLD (Table 1 and 2).

Patient No. 1: A 7-year-old boy was admitted with complaints of psychocognitive dysfunction, absence of speech, irritability, headaches, loss of appetite, frequent colds, general weakness, and fatigue. The child was born from a consanguineous marriage. Considering the anamnesis and the results of immunological and genetic testing, the following diagnosis was made: Primary diagnosis: Cerebellar ataxia with impaired DNA repair - Ataxia-Telangiectasia (Louis-Bar Syndrome), ICD-10: G11.3. This preliminary diagnosis was based on reliable medical history and laboratory findings. As a result, immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IVIG) was initiated using Octagam at a dose of 15-20 g/L, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Genetic findings: A homozygous pathogenic variant in the ATM gene, c.6658C>T (p.Gln2220*), was identified in Exon 46. This sequence change introduces a premature stop codon (p.Gln2220*), which is expected to result in an absent or truncated ATM protein. Loss-of-function variants in ATM are known to be pathogenic (PMID: 23807571, 25614872). This variant is listed in ClinVar (Variation ID: 407464) and has been reported in individuals with ataxia-telangiectasia (PMID: 26896183, 32095276).

Patient No. 2 - Carrier: A 12-year-old girl, born from a consanguineous marriage (in the 3rd-4th generation). According to the parents, diarrhea and delayed psychomotor development were noted since birth. Currently, she presents with unsteady gait, speech impairment, and frequent infectious episodes. General condition: severe due to the disease. Overall well-being is relatively satisfactory. She has a wet, frequent cough. Scleral telangiectasias, gait unsteadiness (walks with support), postural instability, and hypotonia are present. Skin and mucous membranes are clear. Lymph nodes are not palpable. Tonsils are not visible. In the lungs, breath sounds are conducted throughout all fields, with mixed rales; no shortness of breath. Heart sounds are rhythmic and resonant. Abdomen is soft and painless. Stool is formed. No dysuria. Genetic testing: whole-exome sequencing revealed a heterozygous mutation in the ATM gene: c.8384_8392del. Immunoglobulin replacement therapy was prescribed.

Patient No. 3: A 9-year-old girl, born from a consanguineous marriage (3rd-4th generation). Since the age of 1-2 years, she has had an unsteady gait, and had experienced an infectious episode. Examination revealed lymphopenia. Sanger sequencing was performed, identifying a homozygous ATM mutation: c.8384_8392del. General condition: severe due to the disease, asthenic body type. Normal temperature. Skin is clear. Multiple hyperpigmented spots up to 5 mm are present on the torso. On the forearms and occipital area, there are hyperemic granulomatous lesions up to 5 mm. Lymph nodes show no abnormalities. Mucous membranes are clear. Occasional wet cough. Cardiac function is satisfactory. Abdomen is soft and non-tender. The edge of the spleen is palpable, and the liver is at the costal margin. According to the parents, stool and urination are normal.

Patient No. 4: A 10-year-old girl. Complaints upon admission: weakness, impaired fine motor skills, dark-white spots on the skin, frequent colds, and muscle weakness.

Anamnesis morbi: According to the mother, the child has been ill since early childhood. She is followed by a neurologist with a diagnosis of Louis-Bar syndrome. She regularly receives outpatient and inpatient treatment. The patient has been evaluated by an immunologist. Examinations performed: Brain MRI showed diffuse cerebellar atrophy. Laboratory findings: IgG - 7.91 g/L, IgA - 0.67 g/L. Alpha-fetoprotein - 296 ng/ml. A pathogenic homozygous mutation in the MRE11 gene was detected.

Status praesens objectivus: The general condition of the patient is severe. Consciousness is clear, she walks with support, has gait instability and hypotonia. She is oriented in space and time. Mucous membranes are pale pink, skin is dark, multiple hyperpigmented spots less than 5 mm in diameter are present on the torso, and there is redness of the sclerae.

There is no hemorrhagic or edematous syndrome. Subcutaneous fat is poorly developed. The musculoskeletal system has no abnormalities. Chest is of normal shape. Breathing is free, through the nose. Throat is not hyperemic. Lung borders are within normal limits. Auscultation reveals vesicular breath sounds. Percussion shows normal lung boundaries.

Immunoglobulin replacement therapy is recommended monthly. Initial dose: 1 g/kg; in subsequent months: 0.5-0.8 g/kg. She is admitted to the day hospital with a referral for a globulin treatment course.