Scapular Dyskinesis: A Narrative Review of Biomechanics, Clinical Assessment, and Physiotherapy Interventions

Zehra Miçooğulları MSc1 and Mehmet Miçooğulları PhD2*

1Cyprus International University, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation, Via Mersin 10, 99258, Lefkosa, Turkey, ORCID: 0009-0008-6835-3562

2Cyprus International University, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation, Via Mersin 10, 99258, Lefkosa, Turkey, ORCID: 0000-0001-9044-0816

*Corresponding author

*Mehmet Miçooğulları, Cyprus International University, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitat ion, Via Mersin 10, 99258, Lefkosa, Türkiye

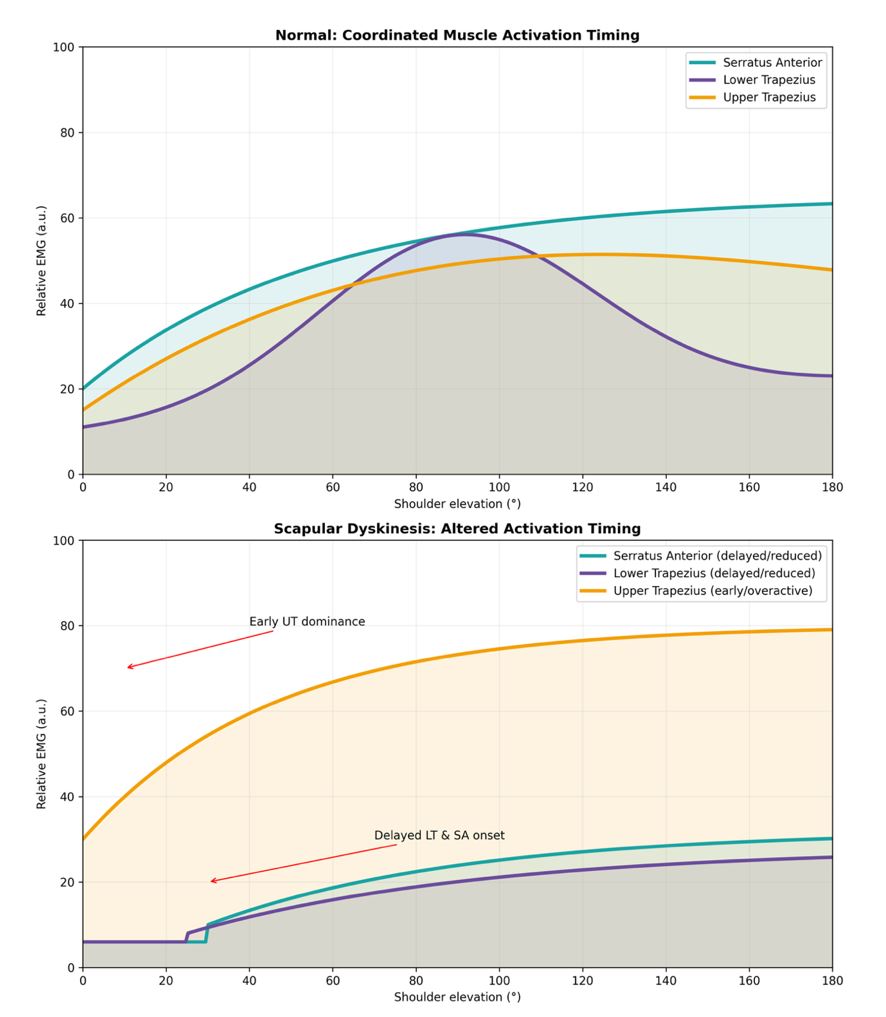

Figure 1: Muscle Activation Timing in Scapular Dyskinesis.

- Matsui K, Tachibana T, Nobuhara K, Uchiyama Y (2018) Translational movement within the glenohumeral joint at different rotation velocities as seen by cine MRI. Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics 5(1): 7.

- Panagiotopoulos AC, Crowther IM (2019) Scapular Dyskinesia, the forgotten culprit of shoulder pain and how to rehabilitate. SICOT-J 5: 29.

- Kibler WB, Sciascia A (2010) Current concepts: scapular dyskinesis. British journal of sports medicine 44(5): 300-305.

- Paine R, Voight ML (2013) The role of the scapula. International journal of sports physical therapy 8(5): 617.

- Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB (2000) Shoulder injuries in overhead athletes: the “dead arm” revisited. Clinics in sports medicine 19(1): 125-158.

- Carnevale A, Longo UG, Schena E, Massaroni C, Lo Presti D, et al. (2019) Wearable systems for shoulder kinematics assessment: A systematic review. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 20(1): 546.

- Kibler BW, Sciascia A, Wilkes T (2012) Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder injury. JAAOS-journal of the American academy of orthopaedic surgeons 20(6): 364-372.

- Kibler WB (2012) The scapula in rotator cuff disease. Med Sport Sci, 57: 27-40.

- Longo UG, Petrillo S, Loppini M, Candela V, Rizzello G, et al. (2019) Metallic versus biodegradable suture anchors for rotator cuff repair: a case control study. BMC musculoskeletal disorders 20(1): 477.

- Paletta Jr, GA, Warner JJ, Warren RF, Deutsch A, Altchek DW (1997) Shoulder kinematics with two-plane x-ray evaluation in patients with anterior instability or rotator cuff tearing. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 6(6): 516-527.

- Warner JJ, Micheli LJ, Arslanian LE, Kennedy J, Kennedy R (1992) Scapulothoracic Motion in Normal Shoulders and Shoulders With Glenohumeral Instability and Impingement Syndrome A Study Using Moire Topographic Analysis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (1976-2007), 285: 191-199.

- Cools AM, Struyf F, De Mey K, Maenhout A, Castelein B, et al. (2014) Rehabilitation of scapular dyskinesis: from the office worker to the elite overhead athlete. British journal of sports medicine 48(8): 692-697.

- Longo U, Risi Ambrogioni L, Berton A, Candela V, Massaroni C, et al. (2020) Scapular Dyskinesis: From Basic Science to Ultimate Treatment. Vol. 17. International journal of environmental research and public health. NLM (Medline).

- Kibler BW, McMullen J (2003) Scapular dyskinesis and its relation to shoulder pain. JAAOS-journal of the American academy of orthopaedic surgeons 11(2): 142-151.

- Roche SJ, Funk L, Sciascia A, Kibler WB (2015) Scapular dyskinesis: the surgeon’s perspective. Shoulder & Elbow 7(4): 289-297.

- Scibek JS, Carcia CR (2012) Assessment of scapulohumeral rhythm for scapular plane shoulder elevation using a modified digital inclinometer. World journal of orthopedics, 3(6): 87-94.

- Phadke V, Camargo P, Ludewig P (2009) Scapular and rotator cuff muscle activity during arm elevation: a review of normal function and alterations with shoulder impingement. Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy 13: 1-9.

- Rockwood CA (2009) The shoulder (Vol. 1). Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Gracitelli MEC, Assunção JH, Malavolta EA, Sakane DT, Rezende MRd, et al. (2014) Trapezius muscle transfer for external shoulder rotation: anatomical study. Acta Ortopédica Brasileira 22(6): 304-307.

- Giphart JE, Brunkhorst JP, Horn NH, Shelburne KB, Torry MR, et al. (2013) Effect of plane of arm elevation on glenohumeral kinematics: a normative biplane fluoroscopy study. JBJS, 95(3): 238-245.

- Ludewig PM, Phadke V, Braman JP, Hassett DR, Cieminski CJ, et al. (2009) Motion of the shoulder complex during multiplanar humeral elevation. JBJS 91(2): 378-389.

- Hannah DC, Scibek JS, Carcia CR (2017) Strength profiles in healthy individuals with and without scapular dyskinesis. International journal of sports physical therapy 12(3): 305-313.

- Burn MB, McCulloch PC, Lintner DM, Liberman SR, Harris JD (2016) Prevalence of scapular dyskinesis in overhead and nonoverhead athletes: a systematic review. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine, 4(2): 2325967115627608.

- Hickey D, Solvig V, Cavalheri V, Harrold M, Mckenna L (2018) Scapular dyskinesis increases the risk of future shoulder pain by 43% in asymptomatic athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine 52(2): 102-110.

- Otoshi K, Takegami M, Sekiguchi M, Onishi Y, Yamazaki S, et al. (2014) Association between kyphosis and subacromial impingement syndrome: LOHAS study. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 23(12): e300-e307.

- Gerr F, Marcus M, Monteilh C (2004) Epidemiology of musculoskeletal disorders among computer users: lesson learned from the role of posture and keyboard use. Journal of Electromyography and kinesiology, 14(1): 25-31.

- Kibler WB, Ludewig PM, McClure PW, Michener LA, Bak K, et al. (2013) Clinical implications of scapular dyskinesis in shoulder injury: the 2013 consensus statement from the ‘Scapular Summit’. British journal of sports medicine 47(14): 877-885.

- Luime J, Koes B, Hendriksen I, Burdorf A, Verhagen A, et al. (2004) Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population; a systematic review. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology 33(2): 73-81.

- Struyf F, Nijs J, Mottram S, Roussel NA, Cools AM, Meeusen R (2014) Clinical assessment of the scapula: a review of the literature. British journal of sports medicine 48(11): 883-890.

- Picco BR, Vidt ME, Dickerson CR (2018) Scapular kinematics by sex across elevation planes. J Appl Biomech 34(2): 141-150.

- Luime JJ, Kuiper JI, Koes BW, Verhaar JA, Miedema HS, et al. (2004) Work-related risk factors for the incidence and recurrence of shoulder and neck complaints among nursing-home and elderly-care workers. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health pp. 279-286.

- Sansone V, Bonora C, Boria P, Meroni R (2014) Women performing repetitive work: is there a difference in the prevalence of shoulder pain and pathology in supermarket cashiers compared to the general female population? International journal of occupational medicine and environmental health 27(5): 722-735.

- McClure P, Greenberg E, Kareha S (2012) Evaluation and management of scapular dysfunction. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review, 20(1): 39-48.

- Ludewig PM, Braman JP (2011) Shoulder impingement: biomechanical considerations in rehabilitation. Manual therapy 16(1): 33-39.

- Oh LS, Wolf BR, Hall MP, Levy BA, Marx RG (2007) Indications for rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® 455: 52-63.

- Van Blarcum GS, Svoboda SJ (2017) Glenohumeral instability related to special conditions: SLAP tears, pan-labral tears, and multidirectional instability. Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review 25(3): e12-e17.

- Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB (2003) The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology Part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy: the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery 19(4): 404-420.

- Sağlam G, Telli H (2022) The prevalence of scapular dyskinesia in patients with back, neck, and shoulder pain and the effect of this combination on pain and muscle shortness. Agri: Journal of the Turkish Society of Algology/Tu? rk Algoloji (Ag? r?) Derneg? i'nin Yayin Organidir, 34(2).

- Nowotny J, Kasten P, Kopkow C, Biewener A, Mauch F (2018) Evaluation of a new exercise program in the treatment of scapular dyskinesis. International journal of sports medicine, 39(10): 782-790.

- Yüksel E (2014) Skapular diskinezisi olan subakromial sıkışma sendromlu olgularda skapular stabilizasyon egzersizlerinin etkinliği Dokuz Eylul Universitesi (Turkey)].

- Shire AR, Staehr TA, Overby JB, Bastholm Dahl M, Sandell Jacobsen J, et al. (2017) Specific or general exercise strategy for subacromial impingement syndrome–does it matter? A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 18(1): 158.

- Khodaverdizadeh M, Mohammad Rahimi N, Esfahani M (2023) A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis: The Effect of Scapular-focused Exercise Therapy on Shoulder Pain and Function and Scapular Positioning in People with Scapular Dyskinesia. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 21(4): 577-590.

- Melo A, Moreira J, Afreixo V, Moreira-Gonįalves D, Donato H, et al. (2024) Effectiveness of specific scapular therapeutic exercises in patients with shoulder pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. JSES reviews, reports, and techniques, 4 (2): 161–174.

- Micoogullari M, Uygur S, Yosmaoglu H (2023) Effect of scapular stabilizer muscles strength on scapular position. Sports Health 15(3): 349–356.