KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDES AND PRACTICES TOWARDS ORAL HYGIENE AND DENTAL CARE AMONG 10-YEAR-OLD PRIMARY SCHOOL CHILDREN IN KITWE, ZAMBIA

Placide Ngoma1,Lilian Chambisha2,Crecious Phiri4and Gabriel Mpundui3,5*

1Mwachichisompola Rural Health Centre, Chisamba, Zambia

2Dental Surgeon, Kitwe Teaching Hospital, Dental Department

3Dental Surgeon, Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital

4Lecturer, Levy Mwanawasa Medical University, School of Public Health

5Lecturer, Levy Mwananwasa Medical University, School of Medicine and Clinical Sciences

*Corresponding author

*Gabriel Mpundu, Dental Surgeon, Levy Mwanawasa University Teaching Hospital, School of Medicine and Clinical Sciences

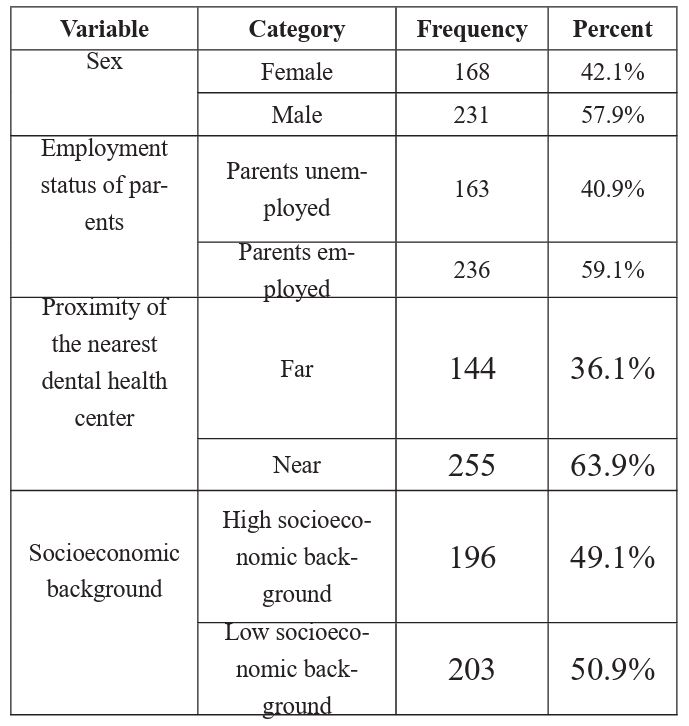

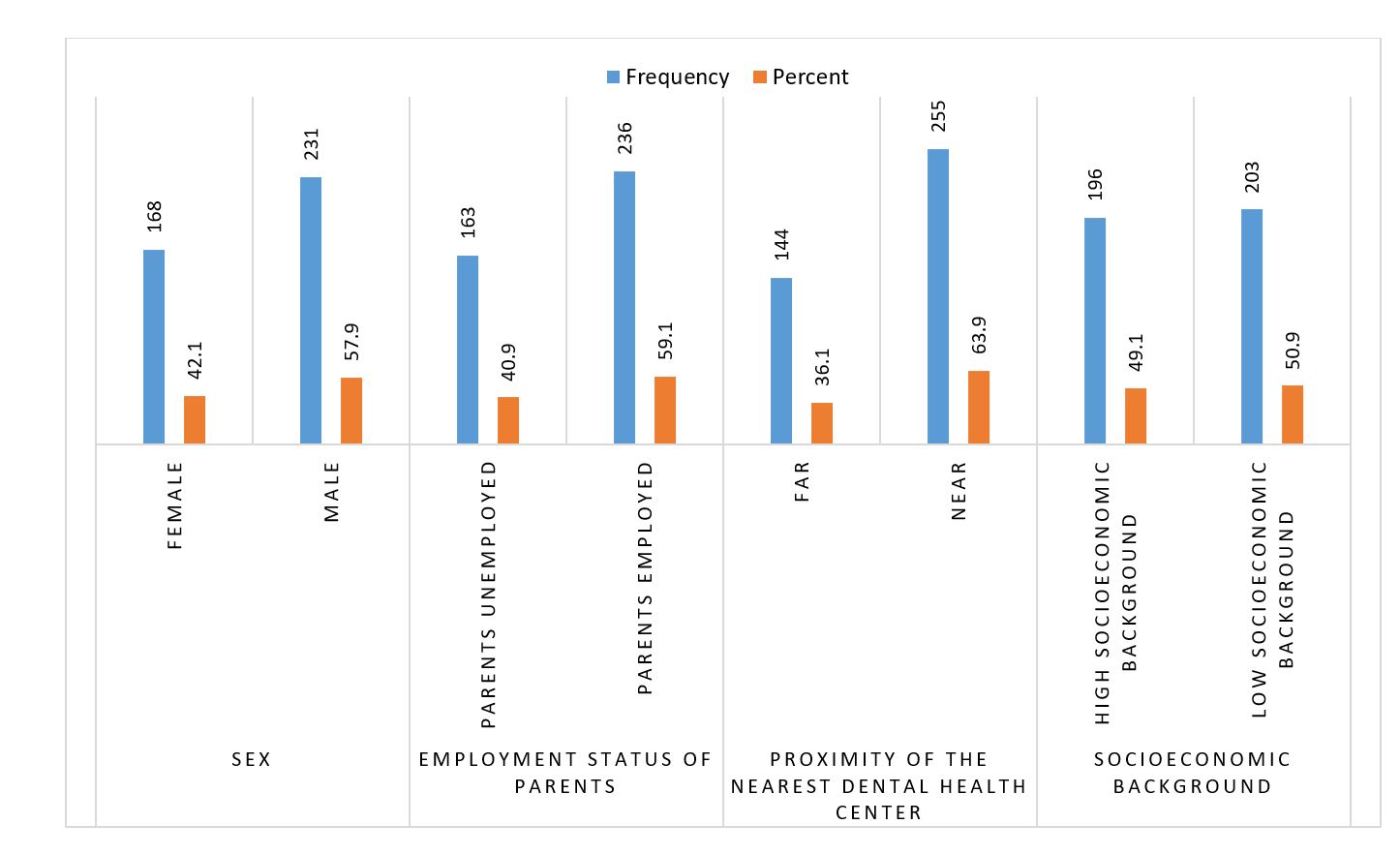

Table 1: Distribution Of Study Participants By Demographic Characteristics (N=399).

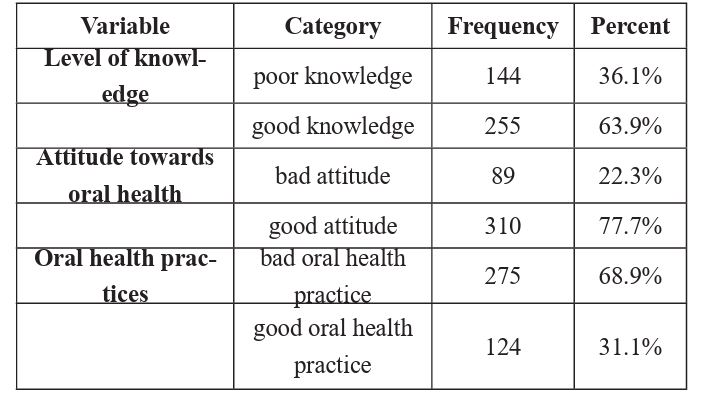

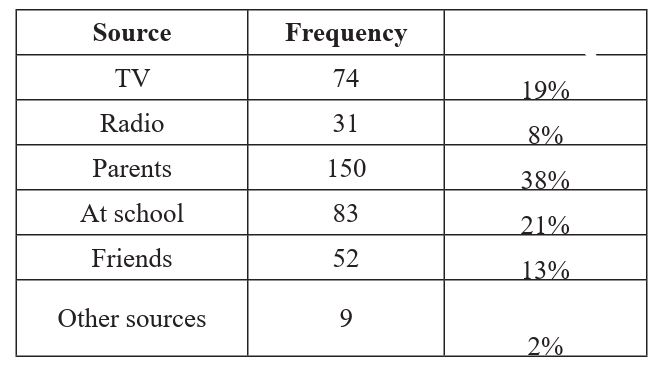

Table 2

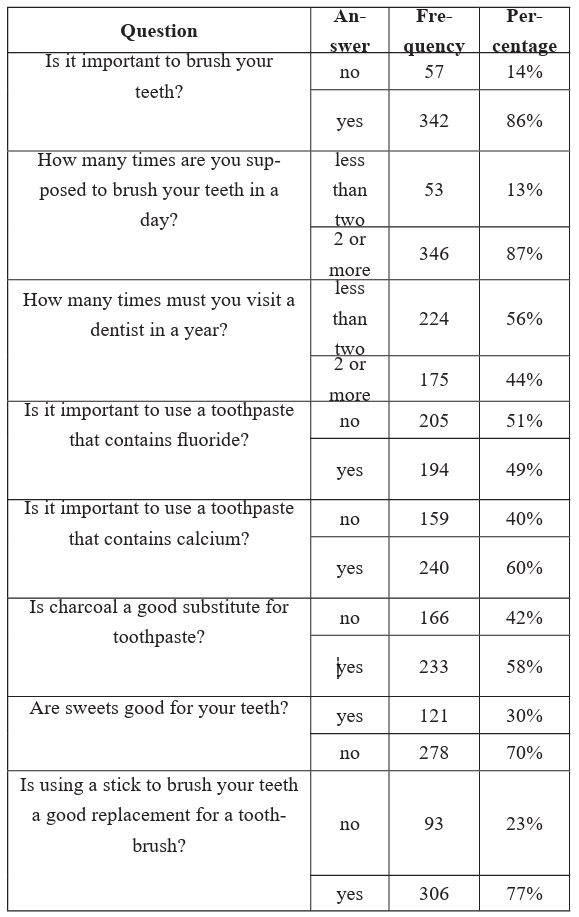

Table 3: Frequency distribution of participants according to knowledge on oral hygiene

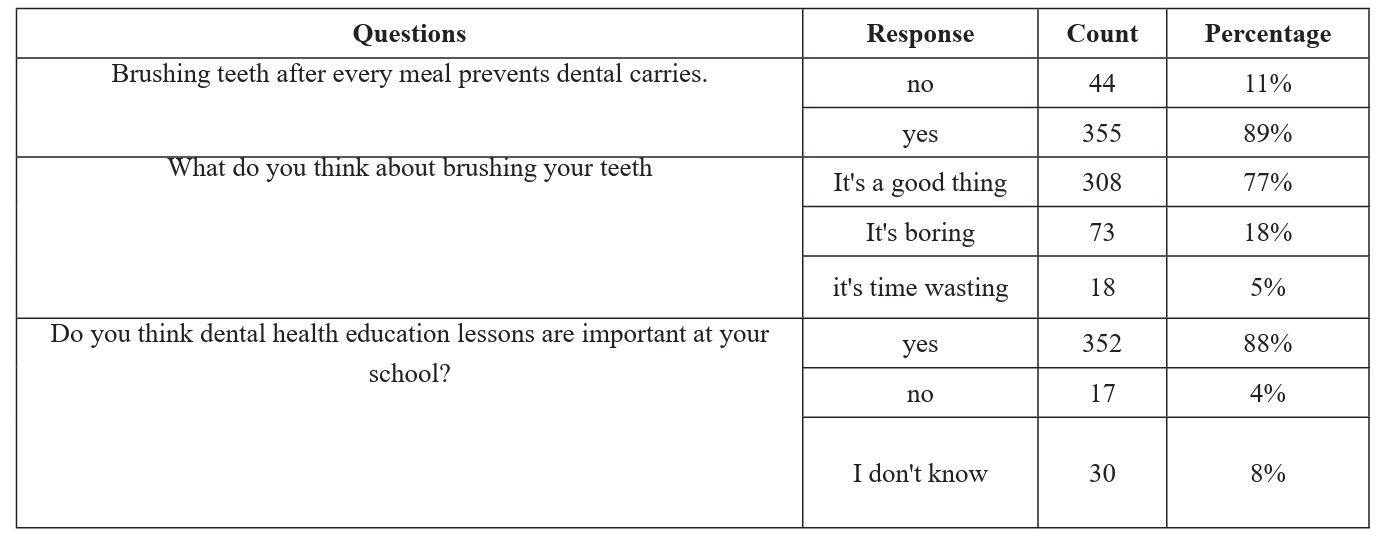

Table 4: Frequency distribution according TO ORAL hygiene attitude

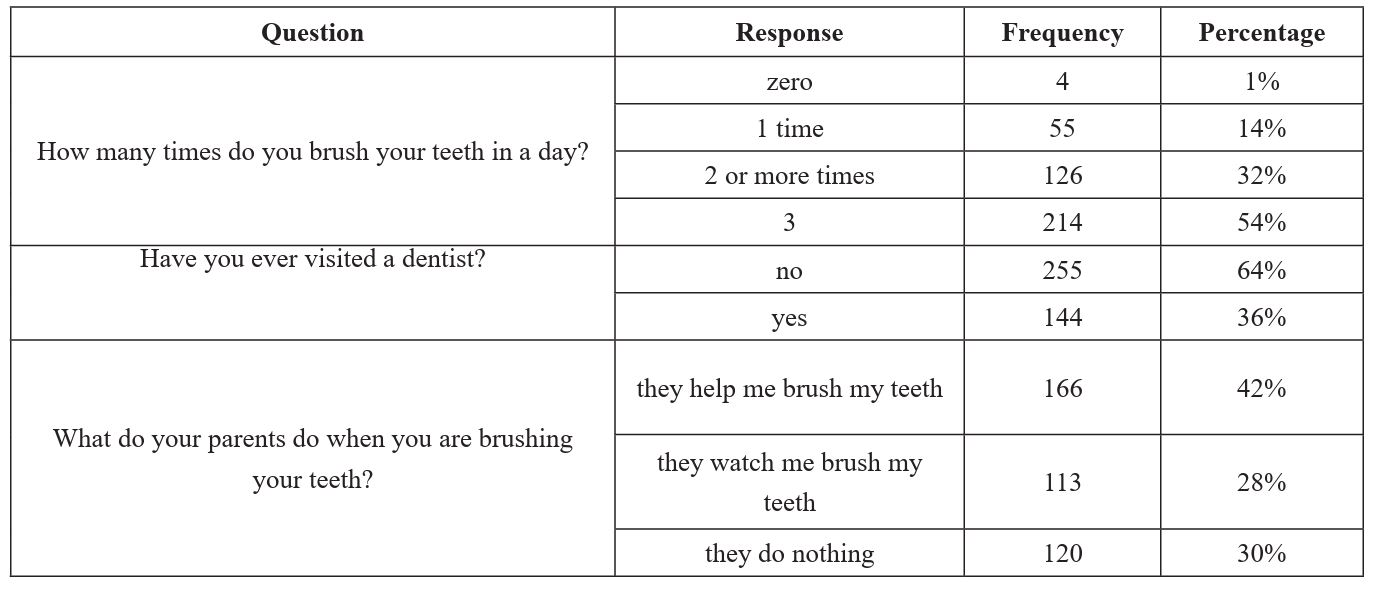

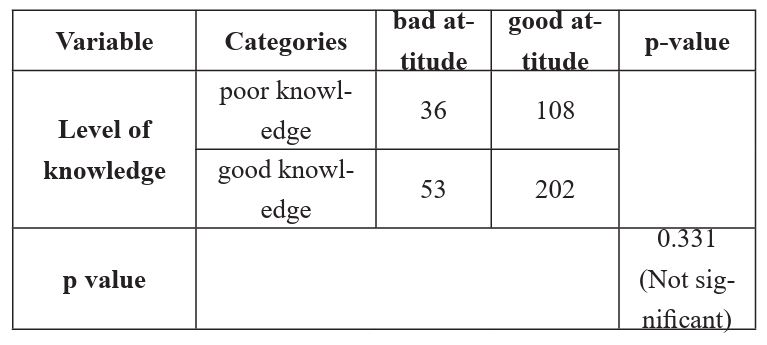

Table 5: Frequency distribution of participants according to oral hygiene practice

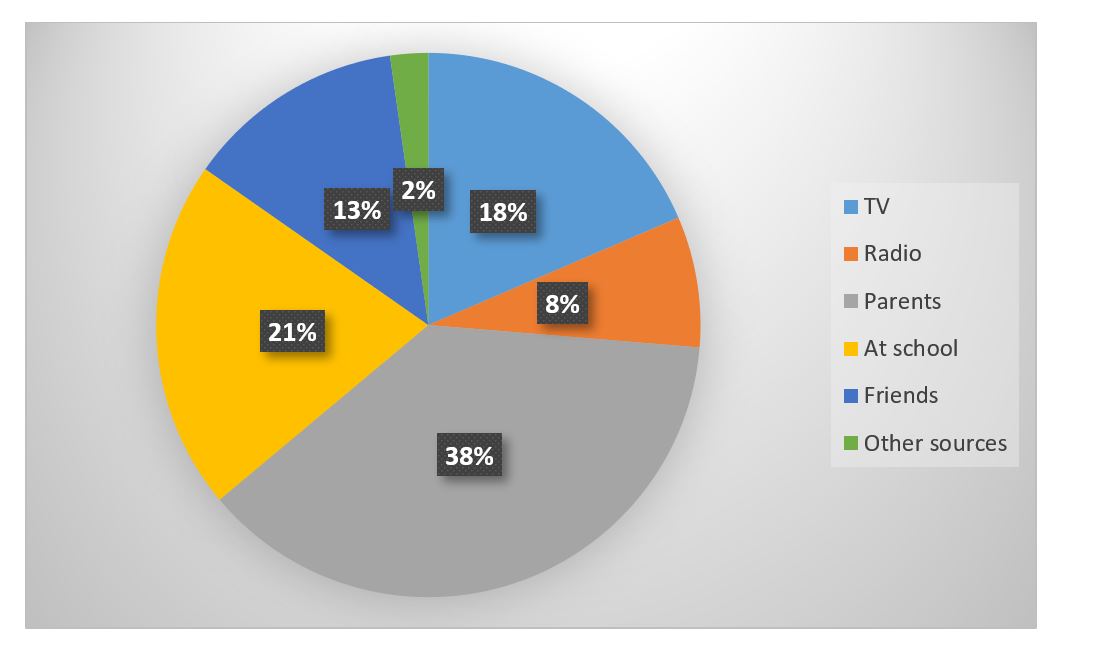

Table 6: sources of knowledge.

Table 7: RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN LEVEL OF KNOWLEDGE AND ORAL HEALTH PRACTICES

Figure 1:Distribution of study participants by demographic characteristics (n=399).

Figure 2: distribution of sources of information on oral hygiene

- Abel SNASS (2015) Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices on Oral hygiene among 12 years old school children in Luanshya, in Zambia. Tanzania Dental Journal, 1(19): 5-11.

- Al-Omar MK, Al-Whaidani AM, Al-Zamazami (2006) Oral hygine knowledge and practice among school children in rural areas. J Dent Educ, 70(2): 178-187.

- Al-Shadan S (2016) Oral health practices and dietary habits of intermediate of the primary to secondary school population. J Allied Health 35(2): 75-80.

- Asiimwe JB (2007) The Effects of HIV/AIDS on Children’s Schooling in Uganda. African population conference, August.

- Aziz Kamran KBHHALZH (2014) Survey of Oral Hygiene Behaviors, Knowledge and Attitude among School Children: A Cross-Sectional Study from Iran. International Journal of Health Sciences, 2(2): 83-95.

- CDC (2016) Center for Disease Control and Preventions: School-Based Dental Sealant Programs. [Online]

- CDC (2017) Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Holt KBR (2013) Oral health and learning: when childrens oral health suffers so does thir learning. 3rd Washington DC: National Materianl on Child Oral Health Resource Center.

- Inc S (2016) How can I make better food choices to prevent tooth decay?.

- Linda Hagberg JS (2007) Knowledge and experience of oral health among secondary school students in Zambia.

- Mohammad Mehdi Naghibi Sistani RYJVAPHM (2013) Determinants of Oral Health: Does Oral Health Literacy Matter?. International Scholarly Research Notices (249591), p. 6.

- Mwaba DP (2012) The Republic of Zambia: National Health Policy, Lusaka: Ministy of Health.

- Neeraja R, Kaylvhizhi E, Honkala S (2009) oral health attitudes and behaviour among a group of students in Bangalore, India. Eur J Dent, 5(7): 163-167.

- Onur Burak Dursun, c. Ş. İ. S. E. T. D. N. Y. M. M. Ö (2016) Mind Conduct disorders in children with poor oral hygiene habits and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children with excessive tooth decay. Archives of Medical Science, 1 December, pp. 1279-1285.

- Parker I, Alkurt M (2011) Oral health attitudes and behaviours among a group of dental studentsin Bangalore. Erur J Dental 3: 163-167.

- Petersen, Bourgeos, ogawa, Ndiaye (2005) The global burden of oral disease and risk to oral health. bulletin of the world health organisation, 661(69): 83.

- Petersen P (2003) Continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century – the approach of the WHO global oral health programme. The world oral health report pp. 661-669.

- Pragya pw, nandita k, hiasharailang l (2016) Assesment of knowledge, attitude and self care among adolescents. journal of clinical and diagnostic research, 10(6), pp. ZC65-ZC75.

- Sara Dakhili, N. O. A. S. S. S. B. M (2014) Association between knowledge and Practice among school going children in Ajman, United Arab Emirates. American Journal of Research Communication, III(10): 39-48.

- Schou L (2000) the relevance of behavioural sciences in dental practices. international dental journal, 50(S6_part1), pp. 324-332.

- Simushi, S. A. N. R. S. S. S., 2018. dental caries on permanent dentition in primary school children. the health press, II(4), pp. 5-16.

- Subait A, Alousaimi A, Shretha M (2017) Oral health knowledge and practice among indeginous Chepagan school children in Nepal. BMC oral health 13(20).

- Suprabha b, Rhao A, shenoy R (2013) utility of knowledge, attitude and practice survey, and prevelence of dental carries among 11 to 13-year-old children in an Urban community in India. Global health 6(1): 359-368.

- Venevive M (2019) DEBS kitwe planning officer [Interview] (17 September 2019).

- WH (2008) World Health Organisation: A guide to developing Knowledge Attitude and Practice Surveys.

- WHO (2015) Oral health.

- WHO (2015) Oral Health: World Health Organisation.

- WHO (2017) WHO: Oral health.

- Zadik Y (2008) Algorithm of first-aid management of dental trauma for medics and corpsmen. dental Traumatology 24(6): 698-701.

- ZDHS (2013-2014) Zambia Demographic and Health Survey, Lusaka: Ministry of Health.