Tension Pneumoperitoneum in the Child: A Report of Two Cases with the Radiologic Features

Shamaki AMB1,Sule MB1*,Erinle SA2,Gele IH3 and Abdullahi A4

1Radiology Department, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto

2Radiology Department, Federal Medical Center, Bida, Niger State

3Radiology Department, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, Sokoto

4Pediatric Department, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, Sokoto

*Corresponding author

*SULE Muhammad Baba, Department of Radiology, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto

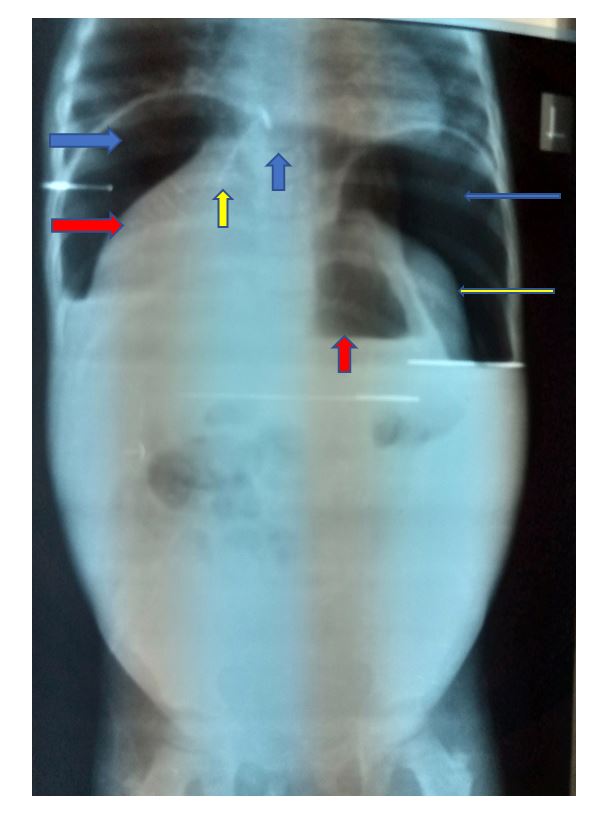

Figure 1: Plain abdominal radiograph; erect view, demonstrating lucencies beneath the hemidiaphragms bilaterally (right and left blue arrows: Cupola sign), inferior and medial displacement of the liver (right red arrow; saddle bag sign) and the spleen (yellow arrow). The continuous diaphragmatic sign with lucency tracking beneath the central tendon of the diaphragm (up blue arrow), falciform ligament sign (displaced falciform ligament by free air: yellow up arrow), and air-fluid level (up red arrow) are also demonstrated. Note: ground glass-opacity in keeping with free intraperitoneal fluid collection in the inferior aspect of the abdomen and pelvic cavity.

Figure 2: Plain abdominal radiograph; supine view, demonstrating bilateral flank fullness of the abdomen (right and left red arrows) oval lucency surrounding by peripheral opacity (Football sign: left blue arrow), the Rigler’s sign (track of lucency outlining both walls of a bowel: red left arrow) and lucency tracking along the paracolic gutter on supine position (yellow left arrow).

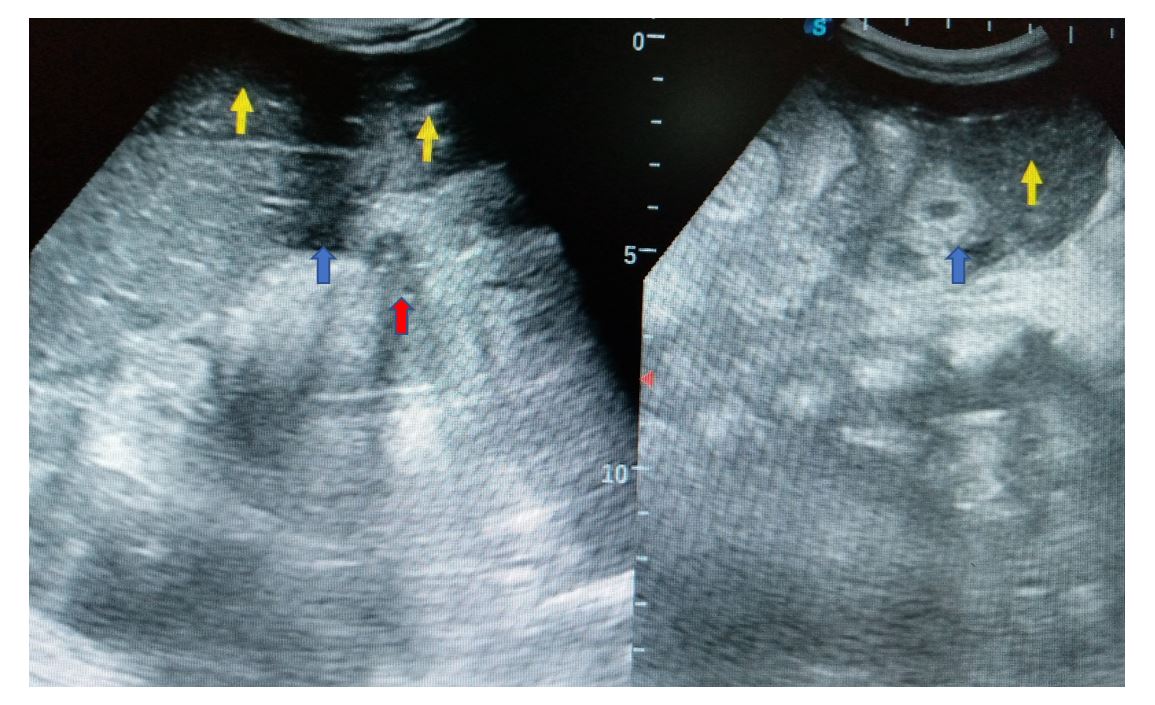

Figure 3: Abdominal ultrasonograms; the left image, demonstrating marked fluid collection in the right subdiaphragmatic area; left yellow up arrow causing inferior displacement of the liver. Free fluid also noted in the Morrison’s pouch (blue up arrow). The right yellow up arrow shows linear shaped echogenic area most likely the comet-tail sign of free air bubble and dirty posterior shadow of pneumoperitoneum (red up arrow). The right image shows pool of free turbid fluid (yellow up arrow) and thick-walled bowel loops (blue up arrow).

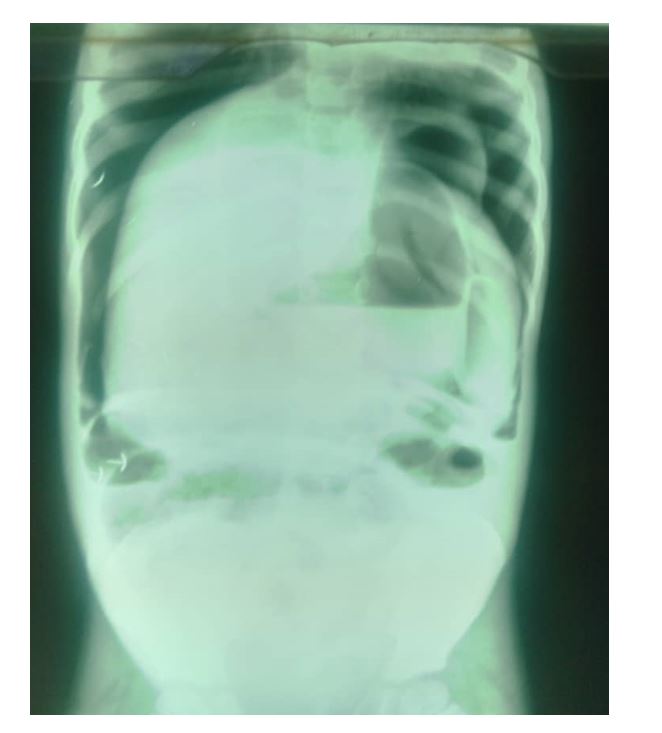

Figure 4: Plain abdominal radiograph; erect view, demonstrating lucencies beneath the hemidiaphragms bilaterally (Cupola sign), inferior and medial displacement of the liver (saddle bag sign) and the spleen. The continuous diaphragmatic sign with lucency tracking beneath the central tendon of the diaphragm, falciform ligament sign (displaced falciform ligament by free air), and air-fluid level are also demonstrated. Note: ground glass-opacity in keeping with free intraperitoneal fluid collection in the inferior aspect of the abdomen and pelvic cavity.

Figure 5: Plain abdominal radiograph; supine view, demonstrating bilateral flank fullness of the abdomen, the Rigler’s sign (track of lucency outlining both walls of a bowel and lucency tracking along the paracolic gutter on supine position with markedly distended bowel loops centrally and peripherally.

- Manuel C, Jaime S, Nicolas C, Daniel G, Erick EV, et al. (2019) Tension pneumoperitoneum: Case report of a rare form of acute abdominal compartment syndrome. Int J Surg Case Rep 55: 112-116.

- Milev OG, Nikolov PC (2016) Non-perforation tension pneumoperitoneum resulting from non-aerobic bacterial peritonitis in previously healthy middle-aged man: a case report. J Med Case Reports 10: 163.

- Chan SY, Kirsch CM, Jensen WA, Sherck J (1996) Tension pneumoperitoneum. West J med 165:61-64.

- Abbas ARM, Turki AAQ, Abdulsalam ABH (2018) Tension Pneumoperitoneum and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Rare Complication of Percutaneous Radiological Gastrostomy, Case Report and Literature Review. GJMR 100: 1-6.

- Brian GG, Frank G (2021) Tension pneumoperitoneum. Radiopaaedia.org. Accessed on March 12, 2021.

- Hutchinson GH, Alderson DM, Turnberg LA (1980) Fatal tension pneumoperitoneum due to aerophagy. Postgrad Med J 56: 516-518.

- Harry W, Vivek B (2018) Massive Pneumoperitoneum Presenting as an Incidental Finding. Cureus 10: e2787.

- Williams NM, Watkin DF (1997) Spontaneous pneumoperitoneum and other nonsurgical causes of intraperitoneal free gas. Postgraduate Med J 73: 531-537.

- Mularski RA, Ciccolo ML, Rappaprt WD (1999) Nonsurgical causes of pneumoperitoneum. West J Med 170:41-46.

- Cecka F, Sotona O, Subrt Z (2014) How to distinguish between surgical and non-surgical pneumoperitoneum? Signa Vitae 9: 9-15.

- Chayla PL, Mabula JB, Koy M, Kataraihya JB, Jaka H, Mshana SE, et al. (2012) Typhoid intestinal perforations at a University teaching hospital in Northwestern Tanzania: A surgical experience of 104 cases in a resource-limited setting. World J Emerg Surg 7: 4.

- Ukwenya AY, Ahmed A, Garba ES (2011) Progress in management of typhoid perforation. Ann Afr Med 10: 259-265.

- Bhutta Z (2006) Curent concepts in the diagnosis and management of typhoid fever. Br Med J 333:78-82.

- Otegbayo JA, Daramola OO, Onyegbatulem HC, Balogun WF, Oguntoye OO (2002) Retrospective analysis of typhoid fever in a tropical tertiary health facility. Trop Gastroenterol 23: 9-12.

- Ugwu BT, Yiltok SJ, Kidmas AT, Opalawa AS (2005) Typhoid intestinal perforation in North Central Nigeria. West Afr J Med 24: 1-6.

- Sharma AK, Sharma RK, Sharma SK, Sharma A, Soni D (2013) Typhoid Intestinal Perforation: 24 Perforations in One Patient. Ann Med Health Sci Res 3: S41-S43.

- Talwar S, Sharma RK, Mittal DK, Prasad P (1997) Typhoid enteric perforation. Aust N Z J Surg 67: 351-353.

- Kim JH, Im J, Parajulee P, Holm M, Espinoza LMC, Poudyal N, et al. (2019) A Systemic Review of Typhoid Fever Occurrence in Africa. Clin Infect Dis 69: S492-S498.

- Grieco M, Polti G, Lambiase L, Cassini D (2019) Jejunal multiple perforations for combined abdominal typhoid fever and military peritoneal tuberculosis. PAMJ 33:51.

- Ugochukwu AI, Amu OC, Nzegwu MA (2013) Ileal perforation due to typhoid fever-Review of operative management and outcome in an urban centre in Nigeria. Int J Surg 11:218-222.

- Sureka B, Bansal K, Arora A (2015) Pneumoperitoneum: What to look for in a radiograh?. J Fam Med Prim Care 4: 477-478.

- Lee CH (2010) Images in clinical medicine. Radiologic signs of pneumoperitoneum. N Engl J Med pp. 362-2410.

- Levine MS, Scheiner JD, Rubesin SE, Laufer I, Herlinger H (1991) Diagnosis of pneumoperitoneum on supine abdominal radiographs. Am J Roentgenol 156: 731-735.

- Khan ZA, Novell JR (2002) Conservative management of tension pneumoperitoneum. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 84: 164-165.

- Schwarz RE, Pham SM, Bierman MI, Lee KW, Griffith BP (1994) Tension pneumoperitoneum after heart-lung transplantation. Am Thorac Surg 57: 478-481.

- Singer HA (1932) Valvular pneumoperitoneum. JAMA 99: 2177-2180.