Management of Severe Hypertriglyceridemia Induced Pancreatitis in Children – A Case Report

Mariana Neto 1,Tiphaine Corbisier2,Catherine Lambert3, Giulia Jannone1, Barbara Murari1, Xavier Stephenne1and Isabelle Scheers1*

1Department of Pediatrics, Pediatric Gastroenterology and Hepatology unit, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium

2Department of Acute Medicine, Pediatric Intensive Care unit, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium

3Department of Hematology, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium

*Corresponding author

*Isabelle Scheers, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Av Hippocrate 10, Brussels 1200, Belgium

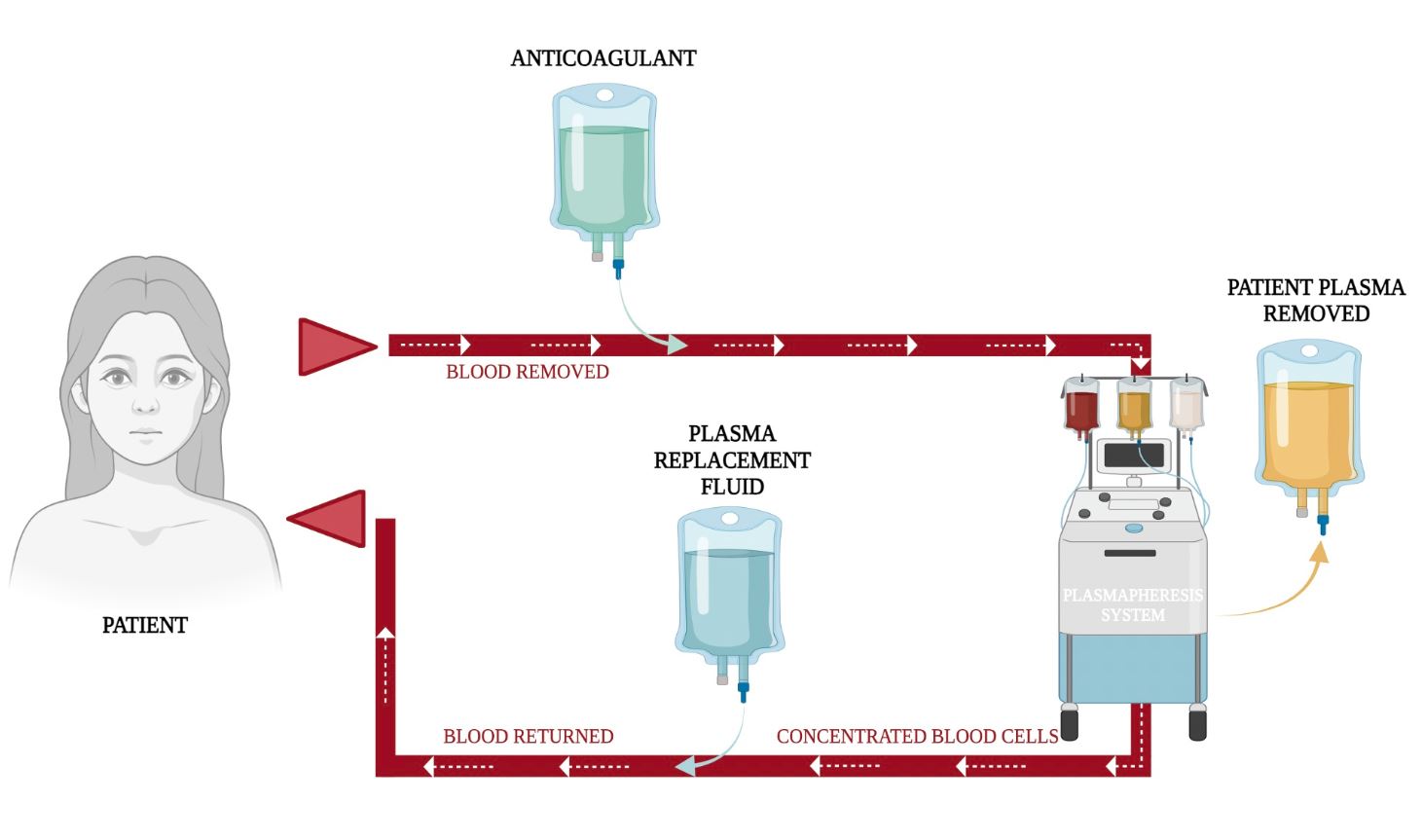

Figure 1: Evolution of serum triglycerides (TG, dark blue line, left y-axis) and lipase (light blue line, right y-axis) levels throughout hospitalization. The x-axis represents the chronological sequence of events, including location of care (Secondary and Tertiary care Hospital) and therapeutic interventions (plasma exchange, insulin and heparin infusion).

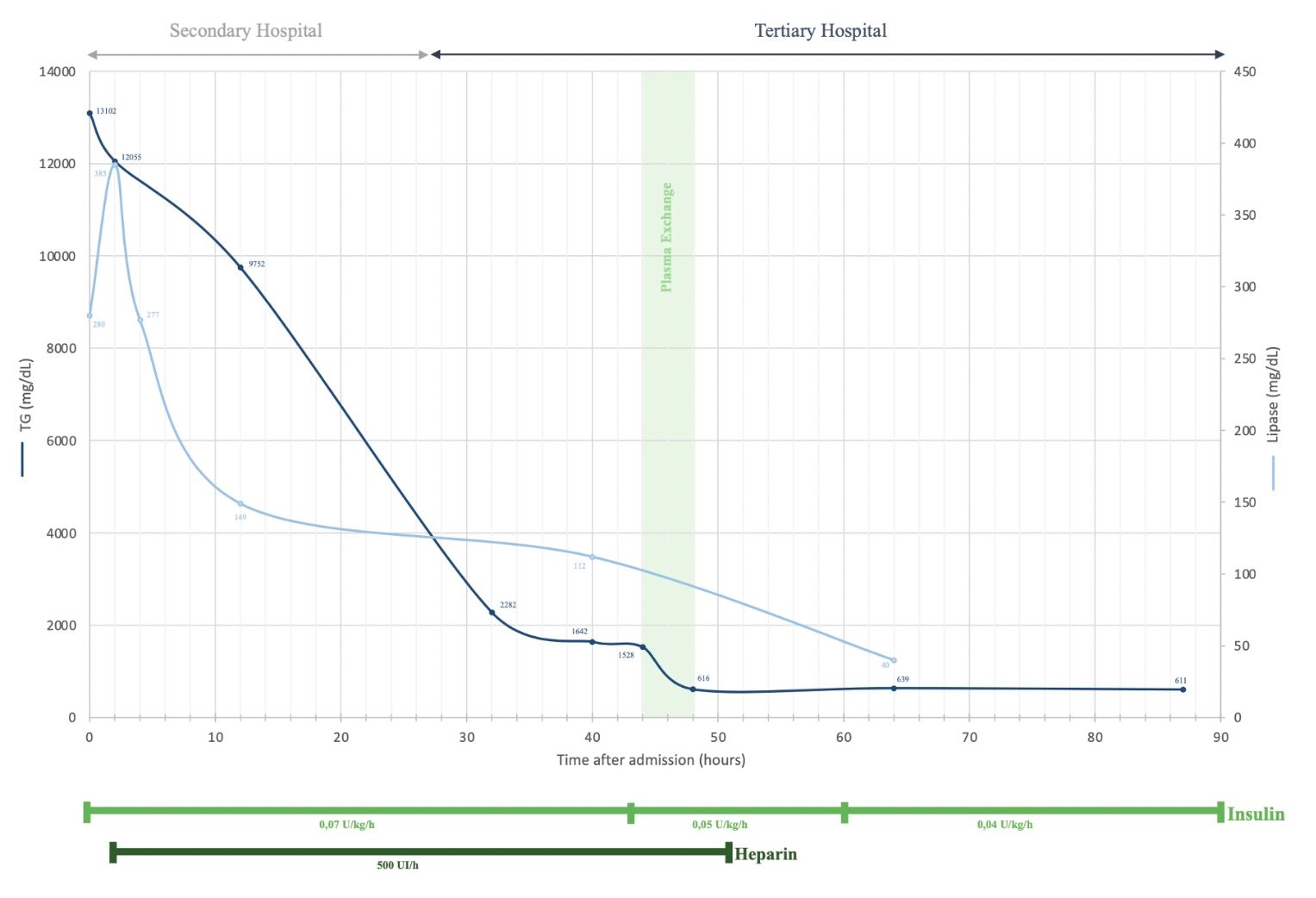

Figure 2: Plasma exchange illustration.

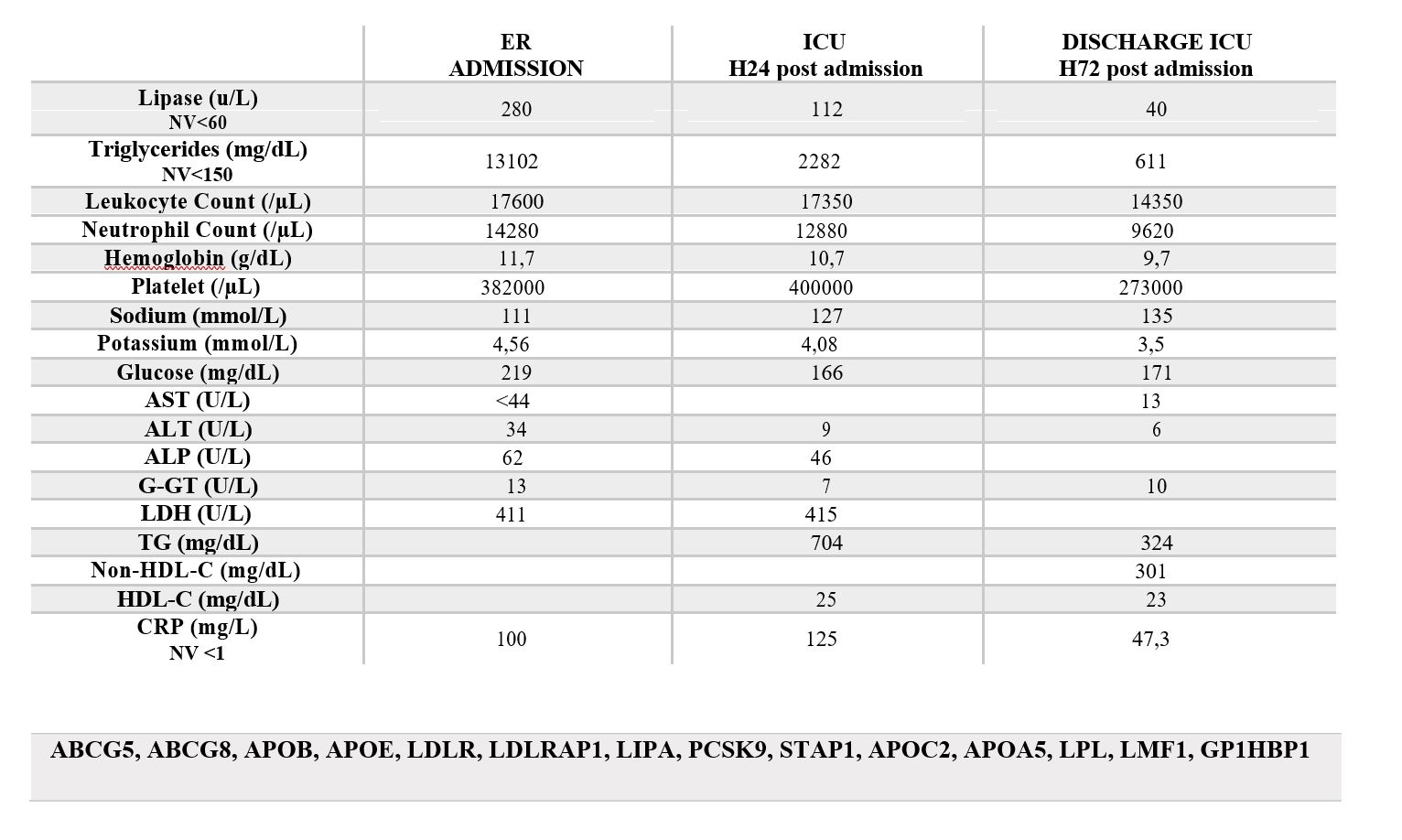

Supplementary Data 1: Laboratory investigations.

Supplementary Data 2: Panel of genes tested by NGS to rule out congenital forms of dyslipidemia.

- Uc A, Husain SZ (2019) Pancreatitis in Children. Gastroenterology 156(7):1969-1978.

- Ippisch HM, Alfaro-Cruz L, Fei L, Zou Y, Thompson T, et al. (2020) Hypertriglyceridemia Induced Pancreatitis: Inpatient Management at a Single pediatric Institution. Pancreas 49(3): 429-434.

- Fredrickson DS (1971) An international classification of hyperlipidemias and hyperlipoproteinemias. Ann Intern Med 75(3): 471-472.

- Tsuang W, Navaneethan U, Ruiz L, Palascak JB, Gelrud A (2009) Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: Presentation and management. Am J Gastroenterol 104(4):984-991.

- Valdivielso P, Ramírez-Bueno A, Ewald N (2014) Current knowledge of hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis. Eur J Intern Med 25(8): 689-694.

- Scherer J, Singh VP, Pitchumoni CS, Yadav D (2014) Issues in hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis: An update. J Clin Gastroenterol 48(3):195-203.

- Bessembinders K, Wielders J, van de Wiel A (2011) Severe Hypertriglyceridemia Influenced by Alcohol (SHIBA). Alcohol Alcohol 46(2):113-116.

- Sandhu S, Al-Sarraf A, Taraboanta C, Frohlich J, Francis GA (2011) Incidence of pancreatitis, secondary causes, and treatment of patients referred to a specialty lipid clinic with severe hypertriglyceridemia: A retrospective cohort study. Lipids Health Dis 10:157

- Lloret Linares C, Pelletier AL, Czernichow S, et al. (2008) Acute pancreatitis in a cohort of 129 patients referred for severe hypertriglyceridemia. Pancreas 37(1):13-18.

- Zhang B, Shi H, Cai W, Yang B, Xiu W (2025) Metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents: definitions, epidemiology, pathophysiology, interventions, and challenges. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 16:1-13.

- Aljenedil S, Hegele RA, Genest J, Awan Z (2017) Estrogen-associated severe hypertriglyceridemia with pancreatitis. J Clin Lipidol 11(1): 297-300.

- Valaiyapathi B, Sunil B, Ashraf AP (2017) Approach to Hypertriglyceridemia in the Pediatric Population. Pediatr Rev 38(9):424-434.

- Grisham JM, Tran AH, Ellery K (2022) Hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis in children: A mini-review. Front Pediatr.

- Garg R, Rustagi T (2018) Management of Hypertriglyceridemia Induced Acute Pancreatitis. Biomed Res Int.

- Nasa P, Jain R, Singh O, Juneja D (2025) Plasmapheresis for Hypertriglyceridemia-induced Acute Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-summary of Case Reports. Indian J Crit care Med peer-reviewed, Off Publ Indian Soc Crit Care Med 29(7): 604-611.

- Lutfi R, Huang J, Wong HR (2012) Plasmapheresis to treat hypertriglyceridemia in a child with diabetic ketoacidosis and pancreatitis. Pediatrics 129(1).

- Ippisch HM, Alfaro-Cruz L, Fei L, Zou Y, Thompson T, Abu-El-Haija M (2020) Hypertriglyceridemia Induced Pancreatitis: Inpatient Management at a Single Pediatric Institution. Pancreas 49(3).

- Joglekar K, Brannick B, Kadaria D, Sodhi A (2017) Therapeutic plasmapheresis for hypertriglyceridemia-associated acute pancreatitis: case series and review of the literature. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 8(4):59-65.