Factors Determining Splenectomy in Cases of Splenic Injuries

Wala Noori Majeed1*, Aous Hani Nie1,Bashar Hadi Shalan1,Hadi Yasir Abbood Aljanabi2,Zahraa Tariq Hasson3,Mohammed Abdullah Jassim4,Ahmed Neamah Abed1and Rania Abd ElMohsen Abo El Nour1,5

1Anaesthesia Techniques Department, College of Health and Medical Techniques, Al-Mustaqbal University, 51001, Babylon, Iraq

2Medical Laboratories techniques Department, College of Health and Medical technique, Al-Mustaqbal University, Babylon 51001, Iraq

3College of Medicine, Al-Mustaqbal University, 51001 Babylon, Iraq

4Aesthetic and Laser Techniques Department, College of Health and Medical technique, Al-Mustaqbal University, Babylon 51001, Iraq

5Community Health Nursing Department, Beni-Suef Health Technical Institute, Ministry of Health, Beni-Suef 62511, Egypt

*Corresponding author

*Wala Noori Majeed, Anaesthesia Techniques Department, College of Health and Medical Techniques, Al-Mustaqbal University,51001, Babylon, Iraq

Figure 1: Distribution of time of surgery against treatment.

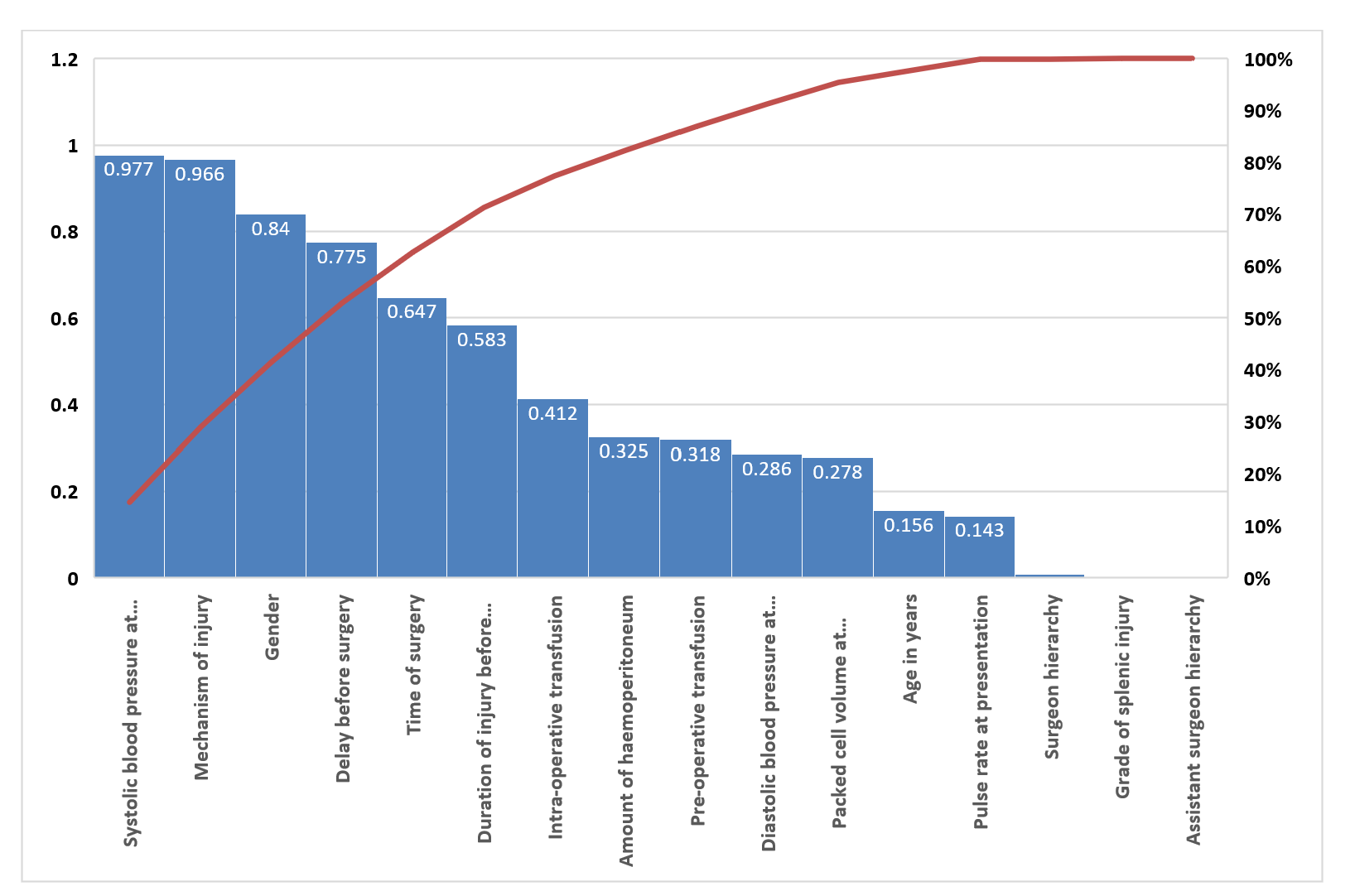

Figure 2: Factors determining splenectomy.

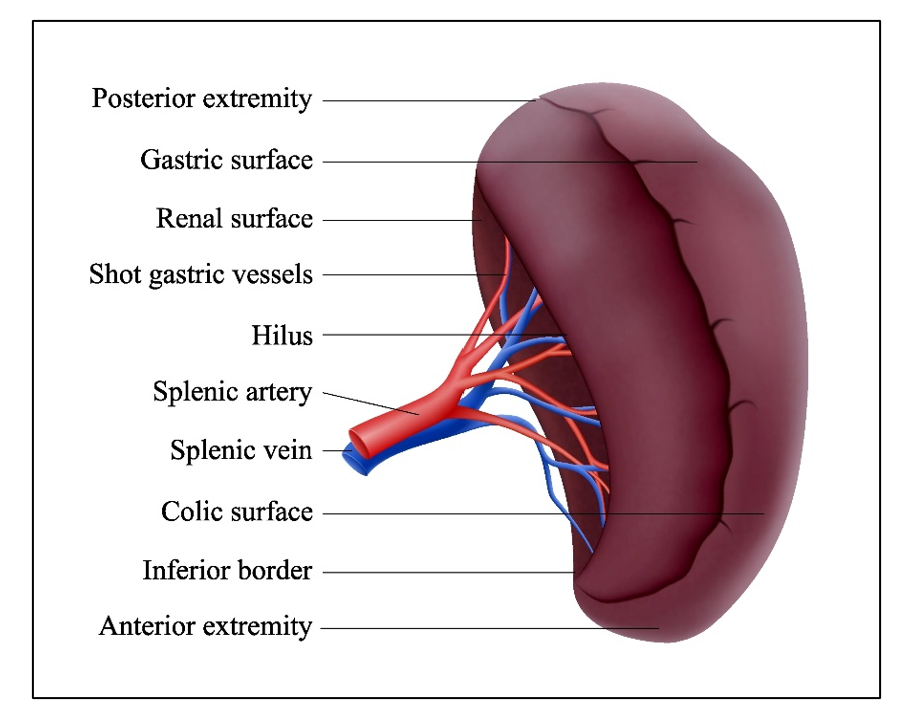

Figure 3: Spleen injured image.

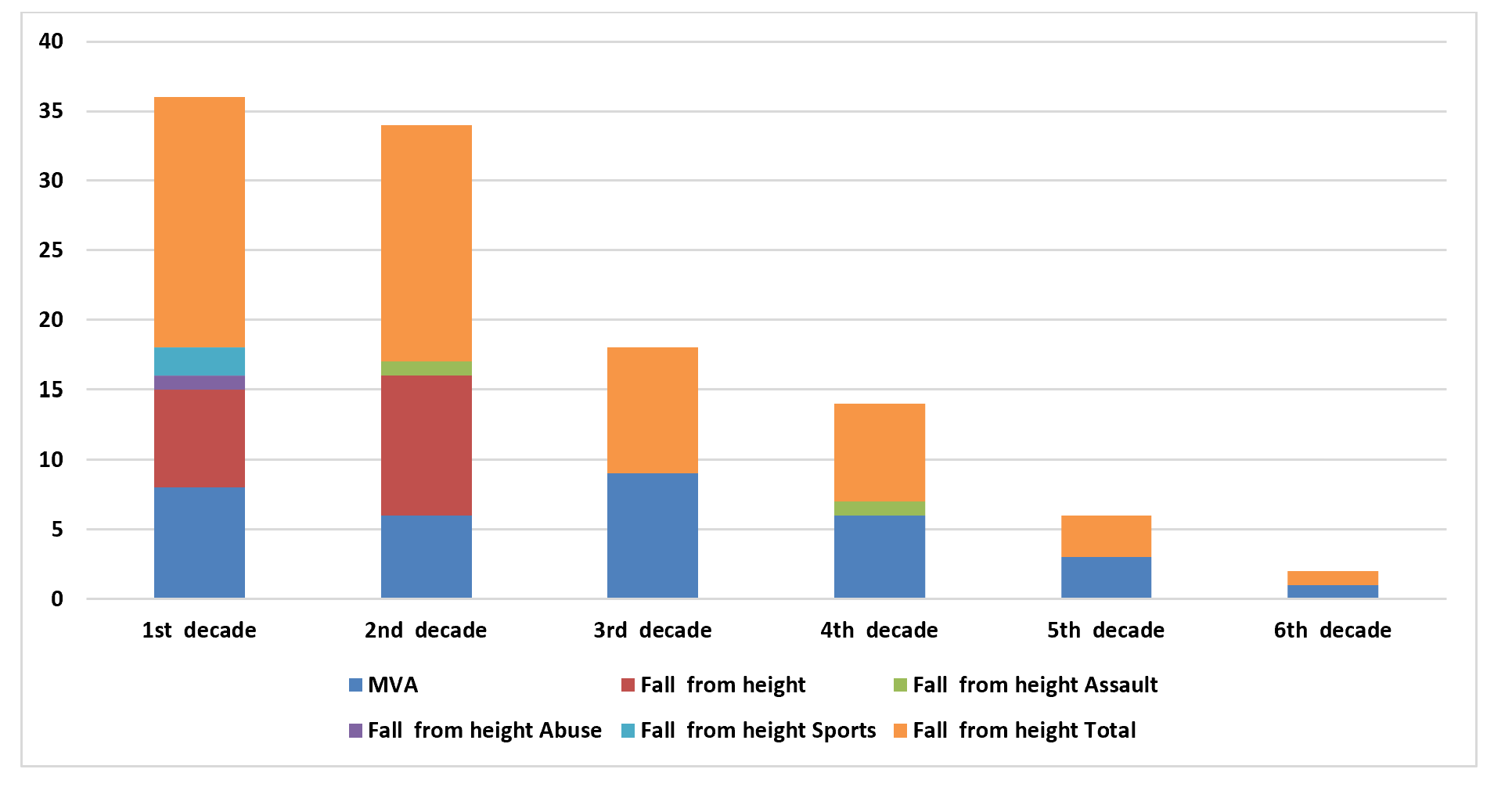

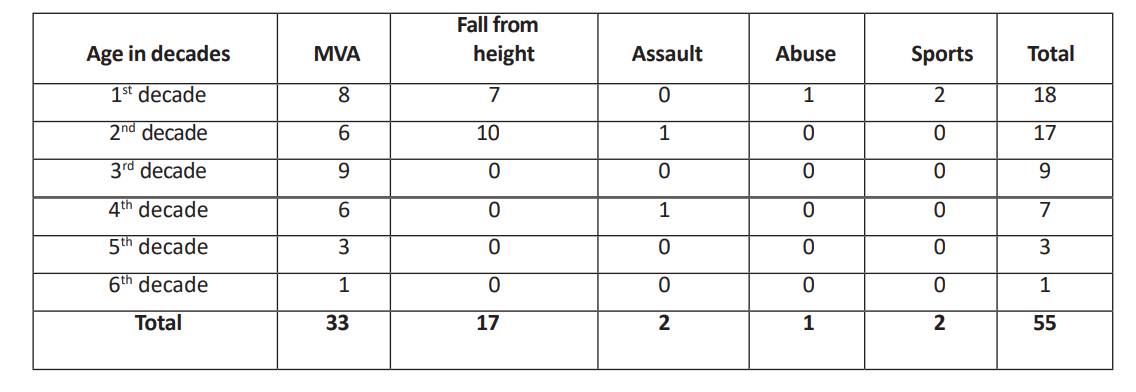

Table 1: The mechanism of injury versus age in decades.

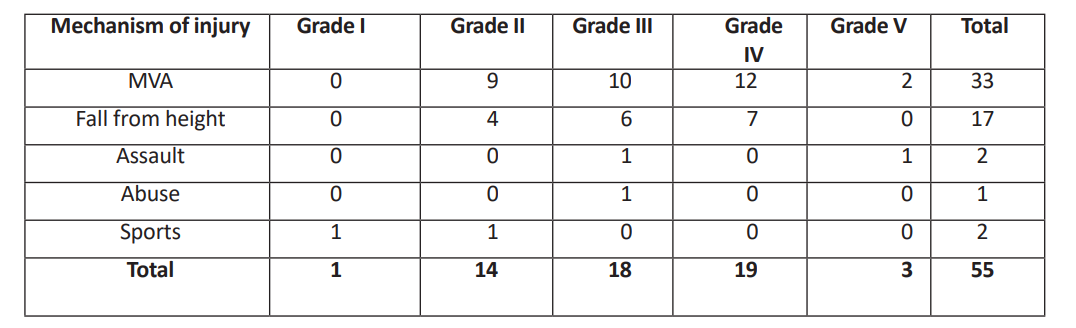

Table 2: Degree of splenic injury V. Mechanism of injury.

- Gaudeuille A, Sacko E, Nali NM (2007) Abdominal trauma in Bangui (Central Africa). Epidemiologic and anatomical aspects. Le Mali Médical 22(2): 19-22.

- Siddique MAB, Rahman MK, Hannan ABMA (2004) Study of abdominal injury : an analysis of 50 cases. TAJ: journal of Teachers Association 17(2): 84-88.

- Nyongole OV, Akoko LO, Njile IE, Mwanga AH, Lema LE (2013) The pattern of abdominal trauma as seen at Muhimbili National Hospital Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. East and Central African Journal of Surgery 18(1): 40-47.

- Ghosh P, Halder SK, Paira SK, Mukherjee R, Kumar SK, Mukherjee SK (2011) An epidemiological analysis of patients with abdominal trauma in an eastern Indian metropolitan city. Journal of the Indian Medical Association 109(1): 19-23.

- Mnguni MN, Muckart DJJ, Madiba TE (2012) Abdominal trauma in Durban, South Africa: factors influencing outcome. International Surgery 97(2): 161–168.

- Asuquo ME, Bassey OO, Etiuma AU, Ugare G, Ngim O (2009) A prospective study of penetrating abdominal trauma at the University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar, Southern Nigeria. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 35(3): 277–280.

- Bairdain S, Litman HJ, Troy M, McMahon M, Almodovar H, Zurakowski D, Mooney DP (2015) Twenty-years of splenic preservation at a level 1 pediatric trauma center. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 50(5): 864–868.

- Zarzaur BL, Rozycki GS (2017) An update on nonoperative management of the spleen in adults. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open 2(1).

- Sladyga A, Benjamin R (2009) An evidence-based approach to spleen trauma: management and outcomes. Acute Care Surgery and Trauma

- Bairdain S, Litman HJ, Troy M, McMahon M, Almodovar H, Zurakowski D, Mooney DP (2015) Twenty-years of splenic preservation at a level 1 pediatric trauma center. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 50(5): 864–868.

- Zarzaur BL, Rozycki GS (2017) An update on nonoperative management of the spleen in adults. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open 2(1).

- Sladyga A, Benjamin R (2009) An evidence-based approach to spleen trauma: management and outcomes. Acute Care Surgery and Trauma

- Coccolini F, Montori G, Catena F, Kluger Y, Biffl W, Moore EE, Ansaloni L (2017) Splenic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. World Journal of Emergency Surgery 12(1): 40.

- Hancock GE, Farquharson AL (2012) Management of splenic injury. BMJ Military Health 158(4): 288–298.

- Carlin AM, Tyburski JG, Wilson RF, Steffes C (2002) Factors affecting the outcome of patients with splenic trauma. The American Surgeon 68(3): 232–239.

- Rose AT, Newman MI, Debelak J, Pinson CW, Morris JA Jr, Harley DD, Chapman WC (2000) The incidence of splenectomy is decreasing: lessons learned from trauma experience. The American Surgeon 66(5): 481–486.

- Pachter HL, Grau J (2000) The current status of splenic preservation. Advances in Surgery 34: 137–174.

- Potoka DA, Schall LC, Ford HR (2002) Risk factors for splenectomy in children with blunt splenic trauma. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 37(3): 294–299.

- Dent D, Alsabrook G, Erickson BA, et al. (2004) Blunt splenic injuries: high non-operative management rate can be achieved with selective embolization. Journal of Trauma 56(5): 1063–1067.

- Wu SC, Chow KC, Lee KH, Tung CC, Yang AD, Lo CJ (2007) Early selective angioembolization improves success of nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury. The American Surgeon 73(9): 897–902.

- Brillantino A, Iacobellis F, Robustelli U, Villamaina E, Maglione F, Colletti O, Noschese G (2016) Non operative management of blunt splenic trauma: a prospective evaluation of a standardized treatment protocol. European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 42(5): 593–598.

- Ekeh AP, Khalaf S, Ilyas S, Kauffman S, Walusimbi M, McCarthy MC (2013) Complications arising from splenic artery embolization: a review of an 11-year experience. The American Journal of Surgery 205(3): 250–254.

- Haan JM, Bochicchio GV, Kramer N, Scalea TM (2005) Nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury: a 5-year experience. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 58(3): 492–498.

- Carlin AM, Tyburski JG, Wilson RF, Steffes C (2002) Factors affecting the outcome of patients with splenic trauma. The American Surgeon 68(3): 232–239.

- Pachter HL, Grau J (2000) The current status of splenic preservation. Advances in Surgery 34: 137–174.

- Carlin AM, Tyburski JG, Wilson RF, Steffes C (2002) Factors affecting the outcome of patients with splenic trauma. The American Surgeon 68(3): 232–239.

- Adesunkanmi AR, Oginni LM, Oyelami OA, Badru OS (2000) Road traffic accidents to African children: assessment of severity using the injury severity score (ISS). Injury 31(4): 225–228.

- Ohanaka EC, Osime U, Okonkwo CE (2001) A five year review of splenic injuries in the University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria. West African Journal of Medicine 20(1): 48–51.

- Alli N (2005) Management of blunt abdominal trauma in Maiduguri: a retrospective study. Nigerian Journal of Medicine 14(1): 17–22.

- Franklin GA, Casos SR (2006) Current advances in the surgical approach to abdominal trauma. Injury 37(12): 1143–1156.

- Gad SM, Sultan T, Dewedar M (2018) Operative versus conservative management of splenic trauma in pediatric patients. Menoufia Medical Journal 31(4): 1145.

- Lui B, Schlicht S, Vrazas J (2004) Role of embolization in the management of splenic trauma. Australasian Radiology 48(3): 401–403.

- Root HD (2007) Splenic injury: angiogram vs. operation. Journal of Trauma 62(6 Suppl): S27.

- Silberzweig JE, Khorsandi AS (2006) Use of splenic artery embolization (SAE) in their splenic injury algorithm. Journal of Trauma 60(3): 686.

- Resende V, Tavares Júnior WC, Kanson MJM, Abrantes WL, Drumond DAF (2003) Non-operative and operative treatment of splenic injuries in children. Revista do Colégio Brasileiro de Cirurgiões 30: 366–373.

- Veger HT, Jukema GN, Bode PJ (2008) Pediatric splenic injury: nonoperative management first! European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 34(3): 267–272.

- Luu S, Spelman D, Woolley IJ (2019) Post-splenectomy sepsis: preventative strategies, challenges, and solutions. Infection and Drug Resistance.

- Forsythe RM, Harbrecht BG, Peitzman AB (2006) Blunt splenic trauma. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery 95(3): 146–151.

- Dunham CM, Cornwell EE III, Militello P (1991) The role of the Argon Beam Coagulator in splenic salvage. Surgery, Gynecology & Obstetrics 173(3): 179–182.

- Stylianos S, Egorova N, Guice KS, Arons RR, Oldham KT (2006) Variation in treatment of pediatric spleen injury at trauma centers versus nontrauma centers: a call for dissemination of American Pediatric Surgical Association benchmarks and guidelines. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 202(2): 247–251.