The Impact of Thalassemia Major on the Endocrine System: A Focus on Growth and Puberty

Hussein Naji Abdullah Alshammari1*, Kareem Abed Mobasher1, Shatha Sahib Asal2, Younis Abdulridha Alkhafaji3, Mohammed Jasim khulaif2 , Miaad Adnan Abdul Salam2 , Maythum Ali Shallan1 , Rawaa Awad Kadhum2 and Rania Abd ElMohsen Abo El Nour2,4

1College of Medicine, Al-Mustaqbal University, 51001 Babylon, Iraq

2Anaesthesia Techniques Department, College of Health and Medical Techniques, Al-Mustaqbal University, 51001, Babylon, Iraq

3Kidney dialysis techniques Department, College of Health and Medical technique, Al-Mustaqbal University, Babylon 51001, Iraq

4Community Health Nursing Department, Beni-Suef Health Technical Institute, Ministry of Health, Beni-Suef 62511, Egypt

*Corresponding author

*Hussein Naji Abdullah Alshammari, F.I.C.M.S Hematology, College of Medicine, Al-Mustaqbal University, 51001 Babylon, Iraq.E-Mail: drhusseinnaji61@gmail.com

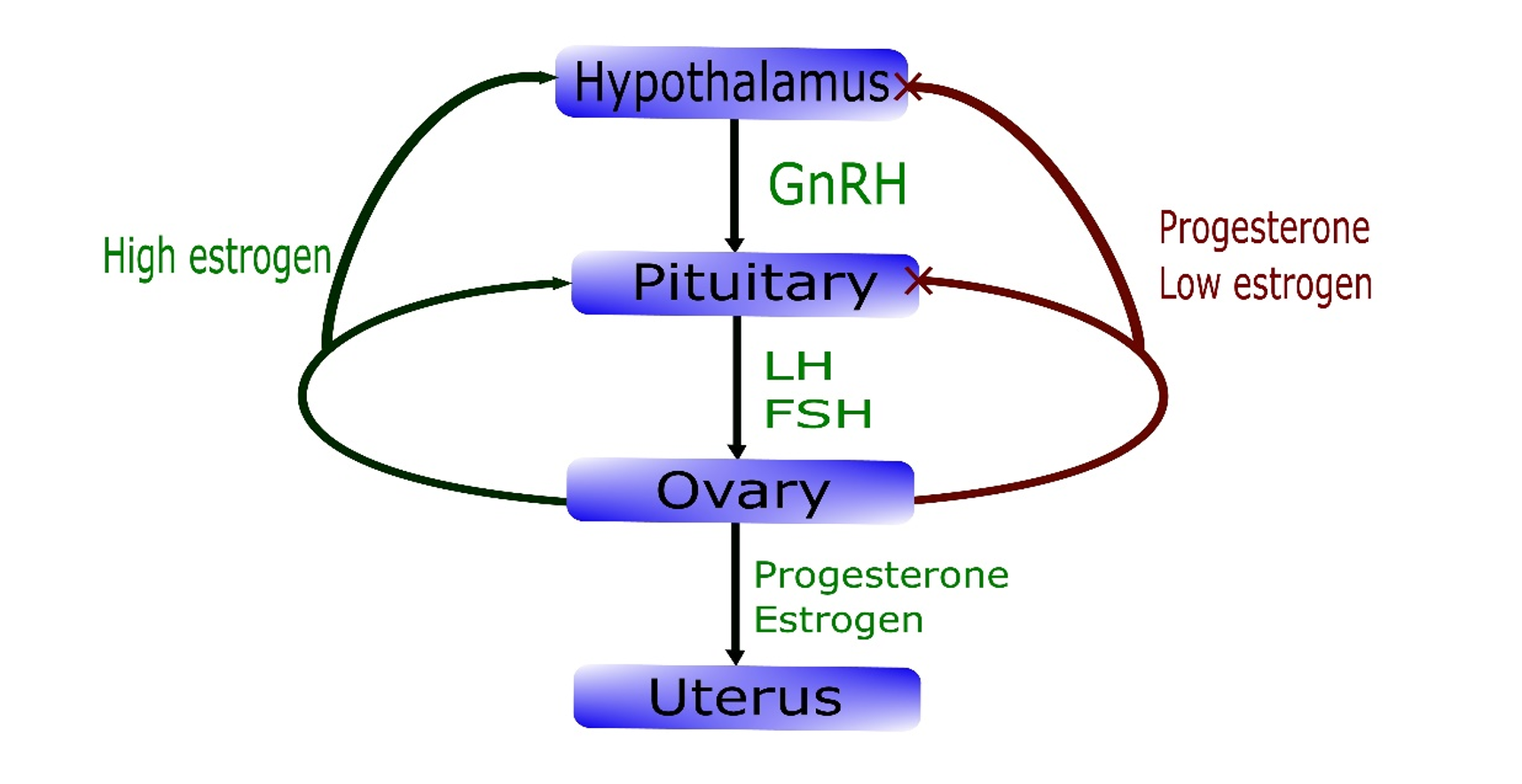

Figure 1: Puberty and pubertal growth spurt in children with beta-thalassemia.

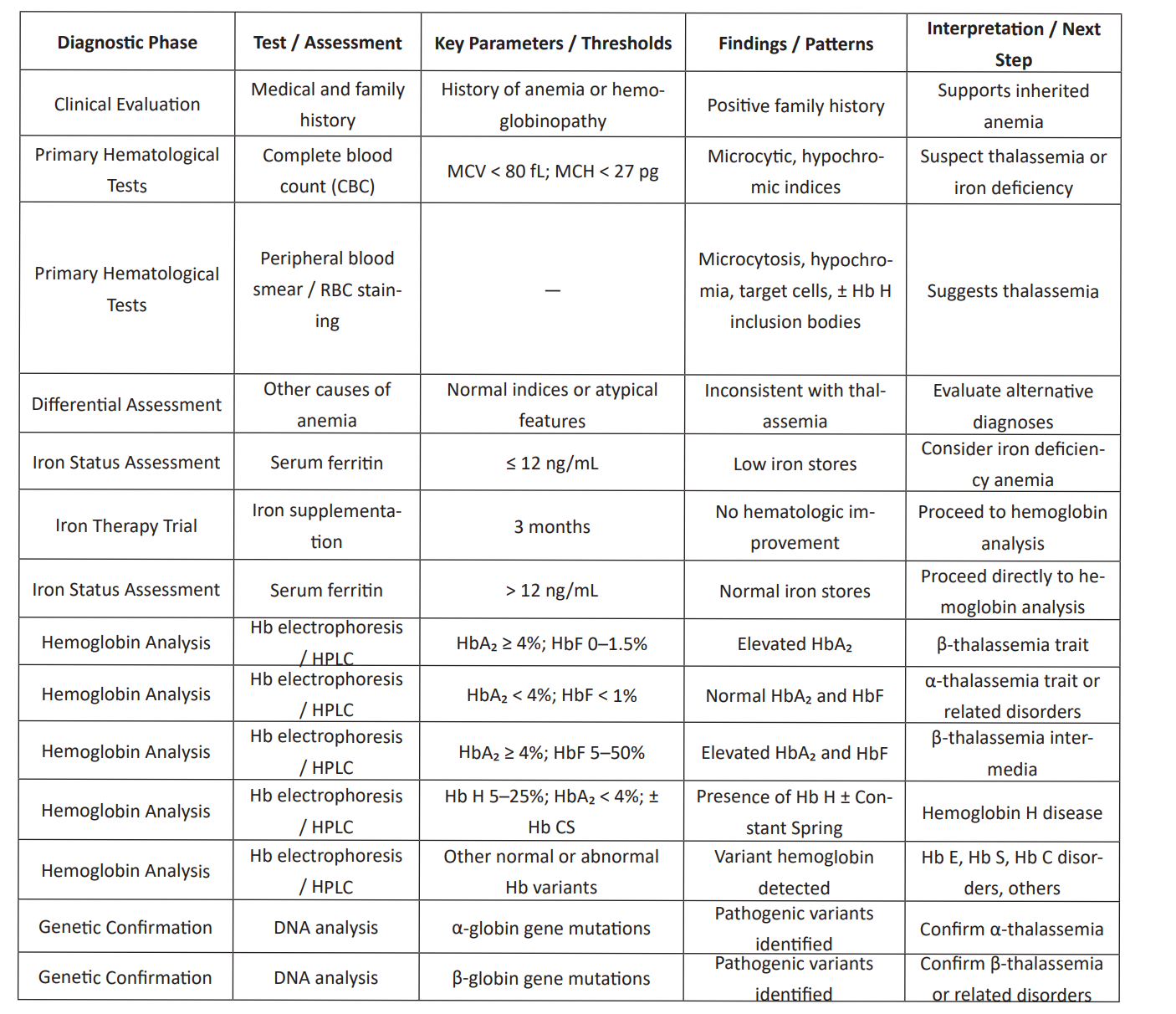

Table 1: Diagnostic Phase of thalassemia.

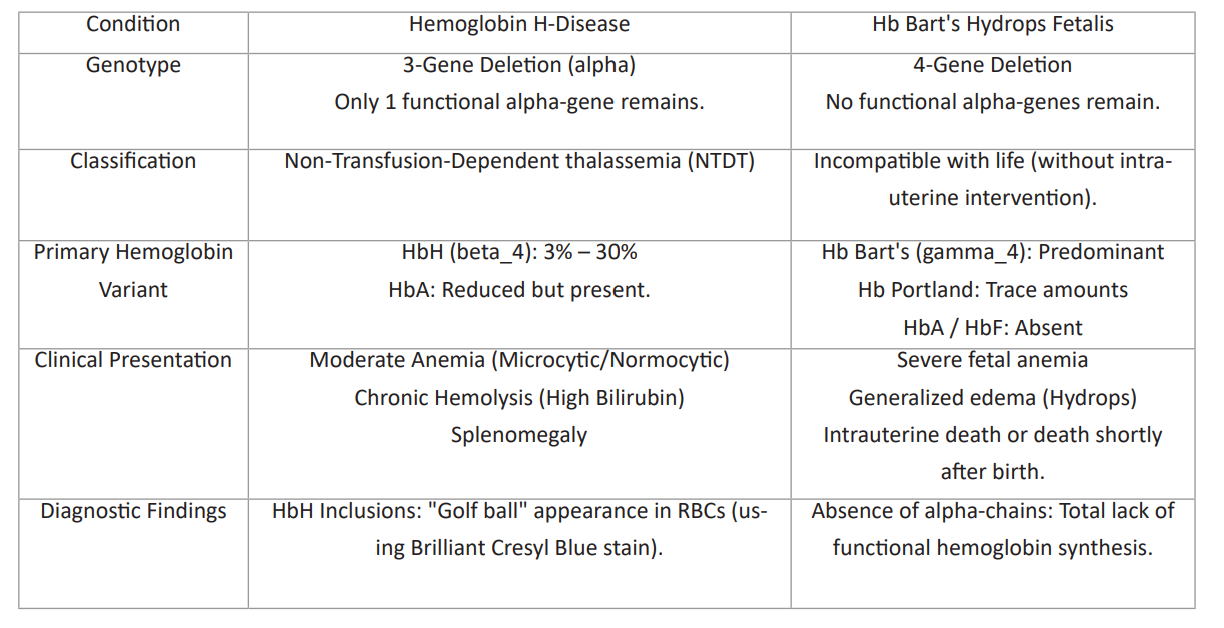

Table 2: Condition of alpha-thalassemia.

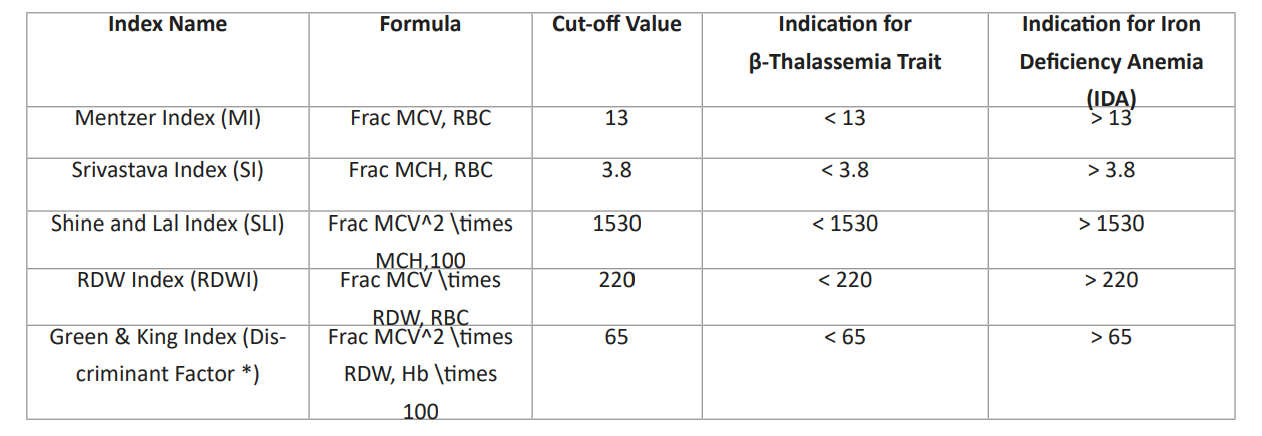

Table 3: Beta-thalassemia carriers.

Note: The "Discriminant factor (DF *)" formula provided in the text (MCV, times (RDW/\Hb,times 100) appears to be a variation of the standard Green & King Index. The standard medical formula includes MCV^2 to achieve the diagnostic cut-off of 65.MCV: Mean Corpuscular Volume (fL)

MCH: Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (pg)

RBC: Red Blood Cell Count (10^12/L)

RDW: Red Cell Distribution Width (%)

Hb: Hemoglobin (g/dL)

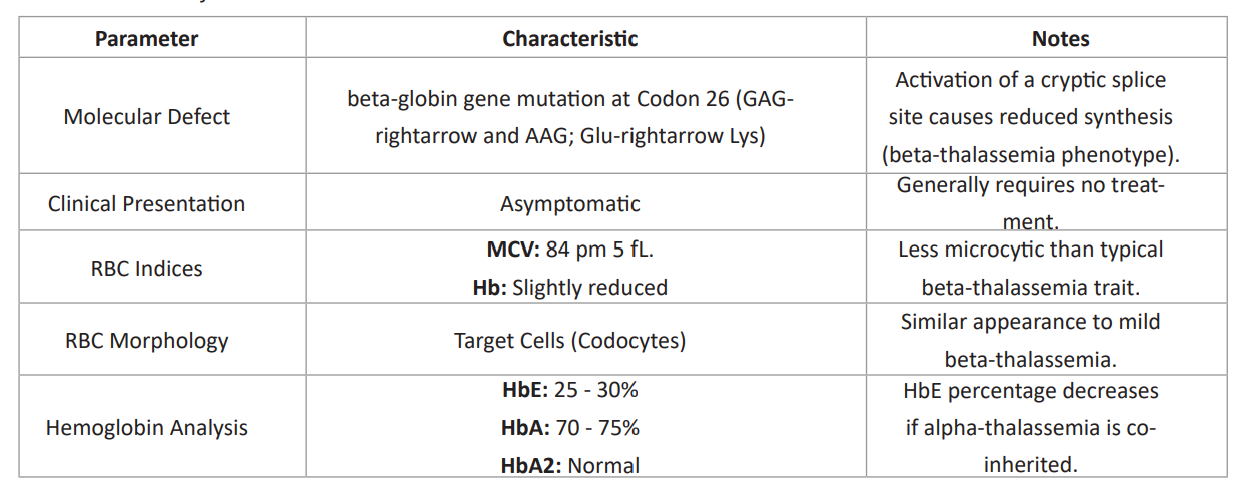

Table 4: Characteristic of HbE carrier.

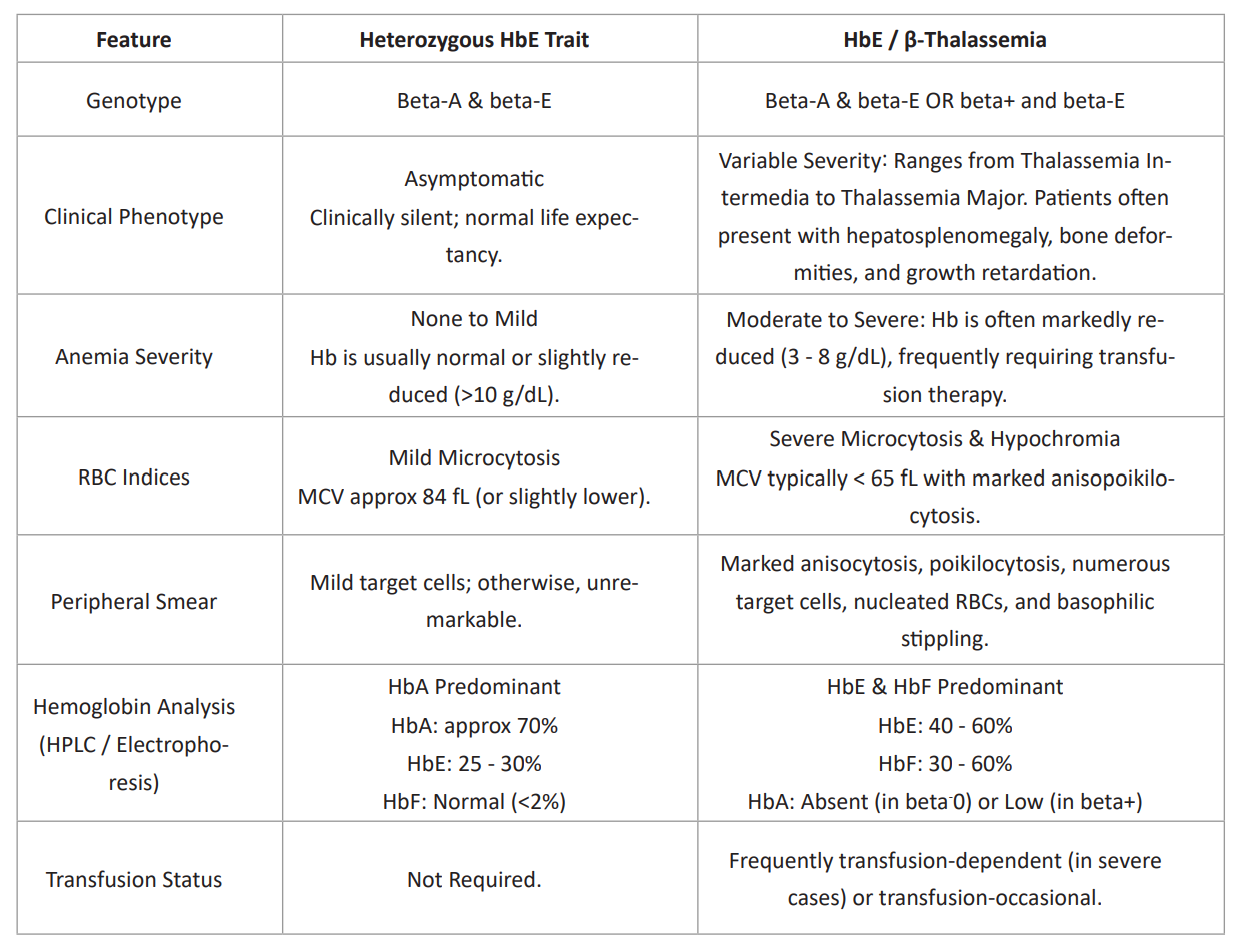

Table 5: Comparative analysis, HbE Trait vs. HbE-beta-Thalassemia.

- Chatterjee R, Bajoria R (2010) Critical appraisal of growth retardation and pubertal disturbances in thalassemia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1202(1): 100–114.

- Carsote M, Vasiliu C, Trandafir AI, Albu SE, Dumitrascu MC, Popa A, Sandru F (2022) New entity—thalassemic endocrine disease: major beta-thalassemia and endocrine involvement. Diagnostics 12(8): 1921.

- Ahmed S, Soliman A, De Sanctis V, Alyafei F, Alaaraj N, Hamed N, Yassin M (2022) A short review on growth and endocrine long-term complications in children and adolescents with β-thalassemia major: conventional treatment versus hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Acta Bio Medica 93(4): e2022290.

- Ghassemi F, Khamseh ME, Sadighnia N, Malek M, Hashemi-Madani N, Rahimian N, Faranoush M (2024) Guideline for the diagnosis and management of growth and puberty disorders in patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia. Iranian Journal of Blood and Cancer 16(1): 43–52.

- Venou TM, Barmpageorgopoulou F, Peppa M, Vlachaki E (2024) Endocrinopathies in beta thalassemia: a narrative review. Hormones 23(2): 205–216.

- Tenuta M, Cangiano B, Rastrelli G, Carlomagno F, Sciarra F, Sansone A, Krausz C (2024) Iron overload disorders: growth and gonadal dysfunction in childhood and adolescence. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 71(7): e30995.

- Tsilionis V, Moustakli E, Dafopoulos S, Zikopoulos A, Sotiriou S, Zachariou A, Dafopoulos K (2024) Reproductive health in women with major β-thalassemia: evaluating ovarian reserve and endocrine complications. Metabolites 14(12): 717.

- Soliman A, Yassin M, Alyafei F, Alaaraj N, Hamed N, Osman S, Soliman N (2023) Nutritional studies in patients with β-thalassemia major: a short review. Acta Bio Medica 94(3): e2023187.

- De Sanctis V, Daar S, Soliman AT, Tzoulis P, Di Maio S, Kattamis C (2023) Retrospective study on long-term effects of hormone replacement therapy and iron chelation therapy on glucose homeostasis and insulin secretion in female β-thalassemia major patients with acquired hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Acta Bio Medica 94(4): e2023195.

- Gagliardi I, Mungari R, Gamberini MR, Fortini M, Dassie F, Putti MC, Ambrosio MR (2022) GH/IGF-1 axis in a large cohort of β-thalassemia major adult patients: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 45(7): 1439–1445.

- Casale M, Baldini MI, Del Monte P, Gigante A, Grandone A, Origa R, Forni GL (2022) Good clinical practice of the Italian Society of Thalassemia and Haemoglobinopathies for the management of endocrine complications in patients with haemoglobinopathies. Journal of Clinical Medicine 11(7): 1826.

- Sahu UP, Kumari Y, Rani N, Hasan O, Mobin N, Soumya S, Kumar N Jr (2025) Functional abnormalities of the endocrine system in beta-thalassemia major patients: insights from a hospital-based observational study. Cureus 17(12).

- Motta I, Mancarella M, Marcon A, Vicenzi M, Cappellini MD (2020) Management of age-associated medical complications in patients with β-thalassemia. Expert Review of Hematology 13(1): 85–94.

- Bhat V, Dar MI, Digra SK, Sharma S (2025) Impact of pretransfusion hemoglobin and ferritin levels on growth and clinical parameters in children with transfusion-dependent thalassemia major. Journal of the Scientific Society 52(3): 283–289.

- Di Maio S, Marzuillo P, Daar S, Kattamis C, Karimi M, Forough S, De Sanctis V (2023) A multicenter ICET-A study on age at menarche and menstrual cycles in patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia who started early chelation therapy. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases 15(1): e2023058.

- de Kloet LC, Bense JE, van der Stoep MYEC, Louwerens M, von Asmuth EGJ, Lankester AC, Hannema SE (2022) Late endocrine effects after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children with nonmalignant diseases. Bone Marrow Transplantation 57(10): 1564–1572.

- Ananvutisombat N, Tantiworawit A, Punnachet T, Hantrakun N, Piriyakhuntorn P, Rattanathammethee T, Charoenkwan P (2024) Prevalence and risk factors predisposing low bone mineral density in patients with thalassemia. Frontiers in Endocrinology 15: 1393865.

- Abdelaziz GA, Elsafi OR, Abdelazeem M (2022) Psychosocial disturbances in thalassemia children. NeuroQuantology 20(18): 1041–1047.

- Adiwinoto RD, Pranoto A, Prayogo AA, Soelistijo SA (2020) Low total testosterone levels in adult male thalassemia major patients: an overlooked complication of iron overload. EurAsian Journal of BioSciences 14(1).

- Yavropoulou MP, Anastasilakis AD, Tzoulis P, Tourni S, Rigatou E, Kassi E, Makras P (2022) Approach to the management of β-thalassemia major associated osteoporosis: a long-standing relationship revisited. Acta Bio Medica 93(5): e2022305.

- Ahmadi M, Rassouli M, Gheibizadeh M, Ebadi A, Asadizaker M (2025) Experiences of Iranian patients with thalassemia major regarding their palliative and supportive care needs: a qualitative content analysis. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery 13(2): 113.

- Rostami T, Mohammadifard MA, Ansari S, Kiumarsi A, Maleki N, Kasaeian A, Ghavamzadeh A (2020) Indicators of male fertility potential in adult patients with beta-thalassemia major. Fertility Research and Practice 6(1): 4.

- Ansharullah BA, Sutanto H, Romadhon PZ (2025) Thalassemia and iron overload cardiomyopathy: pathophysiological insights, clinical implications, and management strategies. Current Problems in Cardiology 50(1): 102911.

- Faranoush M, Faranoush P, Heydari I, Foroughi-Gilvaee MR, Azarkeivan A, Parsai Kia A, Rohani F (2023) Complications in patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia: a descriptive cross-sectional study. Health Science Reports 6(10): e1624.

- Abid F, Husnain M (2025) Micronutrient-endocrine interactions: molecular mechanisms underlying hormonal regulation. Insights of Pakistan, Iran and the Caucasus Studies 4(1): 82–98.

- Bazi A, Poodineh Moghadam M, Baranipour J, Noori Sanchooli H, Soleimani Samarkhazan H, Aval OS, Aghaei M (2025) Vitamin D deficiency as a modulator of outcomes in transfusion-dependent thalassemia: a narrative review. Health Science Reports 8(10): e71383.

- Di Paola A, Marrapodi MM, Di Martino M, Giliberti G, Di Feo G, Rana D, Roberti D (2024) Bone health impairment in patients with hemoglobinopathies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25(5): 2902.

- Jobanputra R, Gandhi AU, Rajani A (2025) Clinical and investigative profile of beta thalassemia major patients visiting a tertiary care center in Gujarat, India. Journal of the Indian Medical Association 123(2): 13–18.

- Zhou X, Huang L, Wu J, Qu Y, Jiang H, Zhang J, Lian Q (2022) Impaired bone marrow microenvironment and stem cells in transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 146: 112548.

- Kazakou P, Nicolaides NC, Chrousos GP (2023) Basic concepts and hormonal regulators of the stress system. Hormone Research in Paediatrics 96(1): 8–16.

- Di Marcello F, Di Donato G, d’Angelo DM, Breda L, Chiarelli F (2022) Bone health in children with rheumatic disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23(10): 5725.

- Basu D, Sinha R, Sahu S, Malla J, Chakravorty N, Ghosal PS (2022) Identification of severity and oxidative stress biomarkers in β-thalassemia patients. Advances in Redox Research 5: 100034.

- Lal A, Viprakasit V, Vichinsky E, Lai Y, Lu MY, Kattamis A (2024) Disease burden and unmet needs in α-thalassemia due to hemoglobin H disease. American Journal of Hematology 99(11): 2164–2177.

- Pinto VM, Forni GL (2020) Management of iron overload in beta-thalassemia patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21(22): 8771.

- Jabeen R, Ansari I, Durrani B, Salman MJ, Mazhar L, Ansari MUH, Ansari SH (2024) Perceptions and experiences of females with β-thalassemia major. Transfusion Clinique et Biologique 31(4): 244–252.

- Tantawy AAG, Tadros MAR, Adly AAM, Ismail EAR, Ibrahim FA, Eldin NMS, Ebeid FSE (2023) Endothelin-1 gene polymorphism and vascular dysfunction in pediatric β-thalassemia major. Cytokine 161: 156048.

- Chia RW, Atem NV, Lee JY, Cha J (2024) Microplastic and human health with focus on pediatric well-being. Clinical and Experimental Pediatrics 68(1): 1.

- Rossi F, Tortora C, Paoletta M, Marrapodi MM, Argenziano M, Di Paola A, Iolascon G (2022) Osteoporosis in childhood cancer survivors. Cancers 14(18): 4349.

- Giordano P, Urbano F, Lassandro G, Faienza MF (2021) Mechanisms of bone impairment in sickle bone disease. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(4): 1832.

- Arumsari DK, Cahyadi A, Andarsini MR, Efendi F, Wardhani ANK, Larasati MCS, Ugrasena IDG (2024) Psychosocial aspects in children with transfusion-dependent thalassemia. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies 19(1): 124–139.